Editor’s note: I have explained basic sports contexts in this post, maybe to an irritating extent.

On February 4th, 2004, I won my first wrestling match.

Every February 4th since, I have taken a moment to recall that day. Until I tried, today, to explain it, I wasn’t really sure why it meant so much to me.

Wrestling is not the athletic theatre you see on TV or in memes; it’s a martial art and organized sport, the most ancient of human competitions. Folk style, the most common form of the sport, has a basic scoring system that lets competitors win by pin, points, or occasionally other technicalities. There are legal and illegal moves, basic attire, no weapons, and few ambiguities.

In my first year of wrestling, as a freshman at Brookline High School, we had a new coach stepping in to fix a struggling program. Head Coach Michael Carver explained to me why wrestling is “the oldest sport, the truest sport, and the greatest sport.” I calmly explained to him that, as a matter of fact, football is the greatest sport. “How’s that going?” he asked.

Indeed, our freshman football team was a historic disaster, going 0-11 (0 wins and 11 losses). But a sad retort was my first wrestling season to date. Heading into February, the final stretch of the three-month season, the three freshmen starters were collectively 0-58, if my math is correct. I was 0-19. I think I’d been pinned every time – the most degrading way to lose. The Yin and Yang of wrestling is no one was accountable for my record except me. The rest of the team came to expect this from the freshmen – losing was just what they did. The two senior captains, meanwhile, rarely lost, earning 30+ win seasons and setting a North Star for what we could become, helping us endure the humiliation. Yin and Yang indeed.

There were many weight classes, and with a thin roster I earned our varsity slot at 119 pounds. Making weight every week, twice a week, added to the challenge of wrestling season, instilling immense discipline for diet and exercise, with as yet no payoff in wins.

There were occasional “forfeits,” which happens when the other team does not have a wrestler at your weight class.

It was only a technicality. But on those few occasions, when the referee would raise my arm to ceremonially declare me the victor and award my team six points, it felt pretty good, like getting the first 600 points on the SAT just for showing up. The first time it happened I walked back to my team bench with a big smile on my face, only to feel it melt off when I made eye contact with Coach Carver, delivering his infamous, devastating scowl.

A lot of work went into that scowl. Every weekday, for two hours, Coach Carver taught us new wrestling moves, had us drill them, conditioned us, and drilled us some more. He studied every one of us and learned what we needed to improve. Every Tuesday he’d coach us through a team match, requiring his early arrival at school and staying until 8pm, and every Saturday he’d wake up hours before dawn, grab the athletic department’s rickety old van, and pick us all up at our houses one at a time to drive us, sometimes hours, to faraway wrestling tournaments. He’d spend extracurricular hours each week, presumably on Sundays, drawing up plans for new trainings, recruiting more wrestlers and assistant coaches, compiling song playlists for practices (a harder task in 2004), painting aggressively inspirational quotes on the wall, and planning events to grow the program. The following year he’d take over as freshman football coach, and we later theorized, not without some evidence, that he only ever did it to recruit more potential wrestlers.

All of the frustration of this hard work came out in these scowls. Without putting us down, Coach Carver never let us think we’d won just by showing up.

Nonetheless, as the the season went on and my losses mounted, I was seeing physical changes and getting stronger. As I improved, hanging on longer in matches, so did our team, winning more team matches and creeping closer to .500 (equal number of wins and losses), which Brookline hadn’t done in years.

A late matchup against divisional opponent Framingham loomed.

Framingham High School’s wrestling team was pretty evenly matched with ours – lacking depth, but with a few talented wrestlers. Coach Carver harped on us for a week leading into this matchup, determined to notch a late season win and show the state Brookline had turned a corner.

February 4th dawned a cold Wednesday. Matches were usually on Tuesday, but Tom Brady had just delivered the New England Patriots’ fanbase its second Super Bowl title, so perhaps it was moved to avoid the traffic surrounding the victory parade. Maybe it also helped us feel a little bit more like anything was possible.

Before any match is the official afternoon weigh-in, which lacks the pomp and pizzazz of a big league boxing or UFC event of the same name, but carries all the same tension. Crafty wrestlers may use the event to puff out their chest, show off their confidence, and intimidate their upcoming opponent. These tactics worked on me as a freshman, oblivious, nervous, and eager for the day to be over with. Mind games prey on the inexperienced.

When it was time for the 119 pounders to weigh in, I looked into the face of my soon-to-be opponent. He was maybe a tad smaller than me, and weighed in a few pounds under – he may have usually been a 112-pound competitor, but was moving up to fill an empty slot in the varsity lineup, a pretty common practice on patchy rosters. He was also similarly young, maybe also a freshman, thin and untoned, and had a look on his face that was vaguely familiar to me.

It took me a moment to realize the familiarity I was recognizing in his wide eyes, with a weak smile, was fear, the same fear I’d felt so many times before as I looked at other, older, stronger wrestlers at weigh-ins who looked so much more comfortable to be there. Drifting into catatonia, I made nothing of this observation.

Thirty minutes later, the match began at the 145-pound weight class. Lars Margolis, one of our senior captains, delivered a usual victory by pin, one of many he’d score on his way to a stellar season that carried him into the All State tournament.

The match rolled through the other weights: 152, 160, 171, 189, 215, 275, 103, and then 112.

I saw my opponent across the gymnasium warming up, just as I was doing the same. Dancing in place, shaking off arms and legs, I saw the same cluelessness in him that I knew in myself – just mimicking the older, more experienced guys. I came to no firm conclusion from this, still locked in my own nerves.

As the 112-pound matchup wrapped up with a Framingham victory, putting them ahead while Coach Carver convulsed in frustration, Assistant Coach David Weingarten scrambled up to me, seemingly as if he’d just finished an espionage mission on my opponent. “This kid’s new, he’s never won a match before!” Weingarten said urgently to me. “You gotta win this one!”

“This is your moment, Greg” said Carver, as he and Weingarten pushed me onto the mat. I could feel the Brookline audience cheering me on, as loud as always. For a moment, I wondered if they really expected something different than the first 19 times they’d seen me walk onto a mat. Then with a twinge of guilt, I wondered if I had as much faith in myself as they had in me.

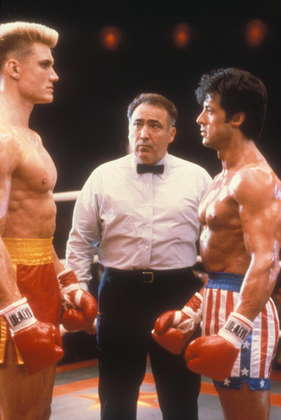

I lined up opposite the kid in front of me, and per the usual rules shook his cold hand. His grip was weak with fright. Like a bizzarro world version of when Ivan Drago met Rocky, I had an inkling that I had met my match, and that it was my destiny to defeat him. But I still had no idea how to win a match, and filled more with nerves than determination. Recalling this now is so silly to me. But I’d never won before.

The ref blew the whistle to start the match.

A wrestling bout often starts with stutter steps and feints. Wrestlers who know what they’re doing try to set up their preferred offense. Wrestlers who don’t just dive into a lockup, an entanglement of the arms.

Within a few seconds, we were in a weak lockup, trading grips of each other’s shoulders and biceps. I didn’t quite feel in control, but I had a unique feeling of not being in someone else’s control too. These two towns weren’t sending their best at this weight class.

As usual, the shouting from the sideline, mostly from coaches but also teammates and fans, was raised to a blurry din. It was just my opponent and me, twirling alone in the loudest silence as we danced a pathetic duet.

In my opponent’s inaction, I was momentarily confused. This isn’t usually how matches went. The audience quieted down, perhaps out of boredom, and I heard Coach Carver’s shouting.

“TAKE A SHOT!”

Oh yeah, the moves we learned in practice! But my opponent took his advice first, dipping and flailing himself at my forward leg in a pathetic shot, which is an entry-level move aimed at basically tackling your opponent, in this case, me. Carver groaned loudly. But two and a half months of newly built instincts had kicked in, and I sprawled, throwing my legs back and landing my body weight on his shoulders. He managed to regain his footing, getting his body out from under me, preventing my scoring a takedown, but in a tit-for-tat instinct deeply rooted as the youngest of three brothers, I returned a shot, successful dropping beneath him and grabbing his right leg with my right arm, before feeling his weight land on top of me in his own sprawl.

No more voices were possible to decipher outside the inner circle of the rubber mat – the yelling of coaches, teammates, and fans on both sides of the gymnasium had returned to total encrypted din in our headgears.

My opponent’s ideal next move would be to try to free his leg by dropping more weight on me, then spinning around behind me, securing bodily control and scoring two points. His subsequent step would then be to get me to my back and keep me there for one second, pinning me to end the match; I didn’t usually last long in this phase. He was making progress, moving around, pulling his own leg further back, and reaching his right arm under my own right leg, making us into a symmetrical puzzle. While the noise was still absolute, I could sense anguish coming from one side, and triumph from the other. The tide had turned against me.

But I wouldn’t relent, holding his leg with my locked right arm. I was stronger than him.

Then something happened, and I can only describe it as thus:

I decided to stop waiting for someone else to win for me.

There is a world of difference between fighting like hell not to lose, versus fighting like hell to win. In my case, I was fighting for something I could not see. I had never won a match before. But at this moment, I chose to win, not having much of an idea of what that would look like, but deciding to go for it anyway.

So I just followed the trainings and live drillings as I’d been taught so many times, under the loving scowl of Coach Carver.

In one great surge, I brought my weight under me, pulling his leg up with both arms, driving my feet into the mat, lifting him up, and taking him back down underneath me, taking full control, emerging on top of him.

Two points. There was an earth-shattering roar from a Brookline bench that I now could see. The walls were shaking.

In control, I sunk my left arm under his, turning it right to go over his neck, aiming to deliver a half-nelson, the first pin move I was taught. But my form was poor, giving him the leverage to resist it and stay flat on the mat, even with less strength. I managed to see the clock – there was less than a minute left in the period, after which we’d reset and he might get favorable positioning. This wasn’t working.

So I brought the arm out, turned to his side as he managed to get back onto all fours, and threw my left arm across his face – legal only as part of a legitimate wrestling move. At the same time I scooped his leg with my right arm. Linking my hands together, I had a cross-face cradle. Now I had to get him to his back.

There’s a normal, careful, and unglamorous way to launch a crossface cradle into a pinning scenario, which involves strength and positioning, and then there’s a reckless, daring, cool fun way which vastly risks one’s advantage, and is known as a “suicide cradle.” Guess which one I did?

“Greg, NO!” came Coach Carver’s shouts through the meteoric noise. “The OTHER WAY!” he screamed.

Instead of lining up next to him and launching us both up over and backwards to our backs, I stayed on my opponent’s side, and dove forward over him (link to a video demonstrating the move at the skill level I had at the time), tucking my head under him, landing momentarily with my back on the mat, holding on for dear victory – if I let go, he’d have me pinned. Instead I dragged his limp body over my somersault as I came up, dragging him onto his back, still locking my arms with his leg and face in between them.

I was in uncharted territory, actually controlling my opponent, navigating his shoulder blades toward the mat. The seconds were winding down.

How I survived all season until this moment, having never yet experienced the victory for which I held out, I cannot recall. To an extent that I was mocked for repeating platitudes to the effect, I took pride in never quitting. I endured and I worked hard. Moreover I was encouraged by seeing older, more experienced wrestlers win many matches and tournaments. I believed if I quit, I’d quit a loser, but if I hung on, I could come to win like they did. So no matter how bad it got I wanted to see it through.

The moment the referee slapped the mat to signal I had scored a victory by pin, I felt three months of tension release, and knew it was all worth it. The whistle blew, the bell could toll, for me too. I had ordained for myself a new reality, in which winning a match, or achieving anything else I wanted for myself in life, was always possible, I just had to choose to take it.

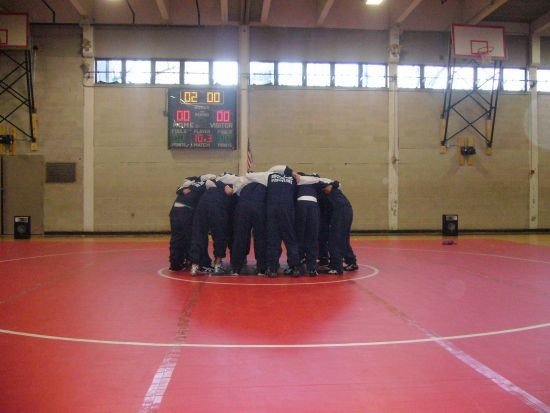

I might not have believed what had just happened, had there not been an uproarious storm of cheers from the Brookline bench. Every wrestler, coach, parent of a wrestler, and attending Brookline fan was on their feet, clapping for me. They knew me and were extolling the vindication of their faith in me, or else dealing with their own disbelief.

“I can’t say enough good things about this team tonight,” said Coach Carver after our 36-32 match victory, later in the locker room – a close enough score that every match mattered. He praised several wrestlers stepping up, scoring pins late in their matches to earn six points instead of three or four, resisting pins by talented opponents, staving off points for Framingham. “But the key victory, the biggest step up tonight, goes to Greg Nasif,” he said, as I smiled shamelessly to more cheers from teammates. “When I told him he had to do it, that we needed a win, he stepped up, found that something within him, and did it. He lost, so, so many matches, to get here,” he said, to laughter. “But every loss is worth it for that first win. And it’s the first win, but not the last, right Greg?”

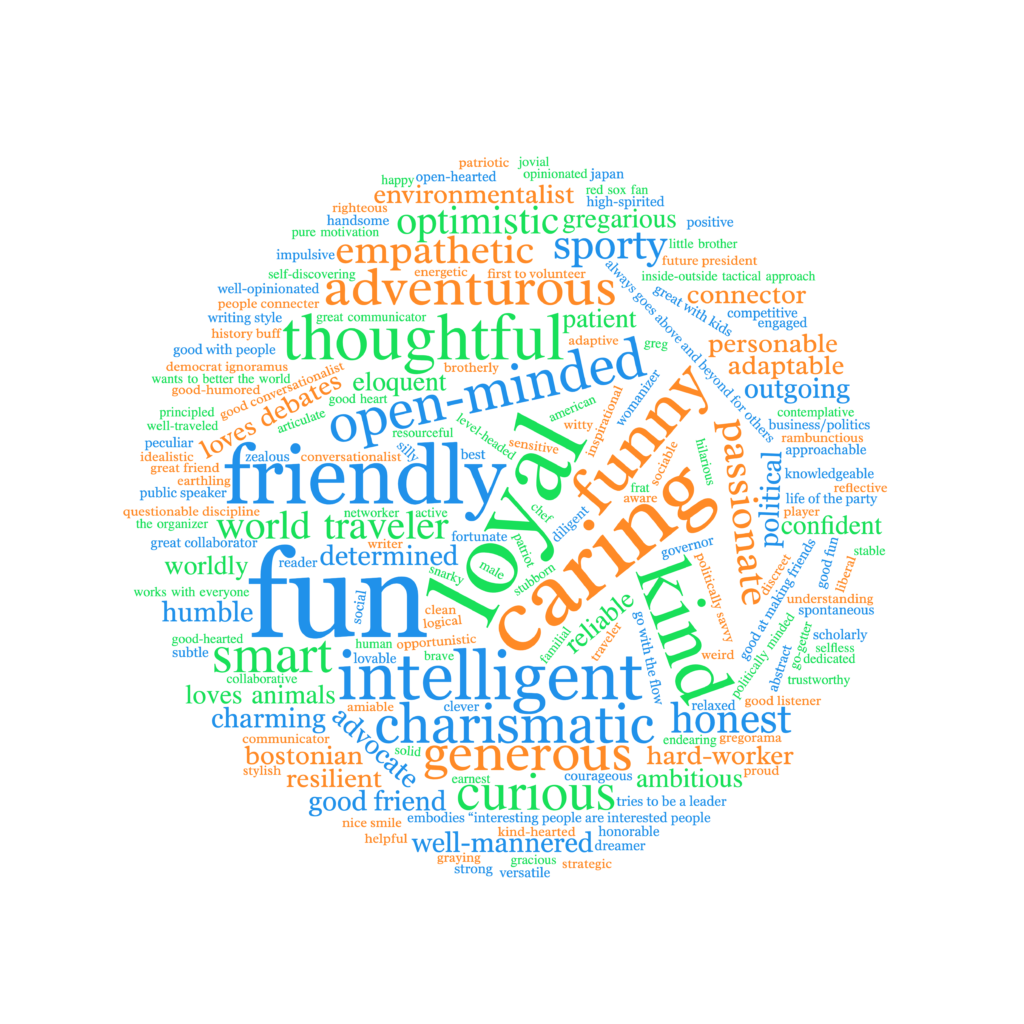

Coach Carver, overjoyed to see his hard work beginning to bear fruit, didn’t know the future when he said those words. He didn’t know his freshman 119-pounder, who would finish the season 1-23, would become a senior captain three years later, going 31-4 at 160 pounds, a conference all-star, beating multiple top-10 statewide wrestlers to break into the All-State tournament, ranking 7th in the state. Nor did he realize my stellar wrestling performance was a tie-breaking credential to knock me off the waitlist and get me accepted to my first college.

He didn’t know what his legacy would mean for the struggling Brookline wrestling program, for which he’d deliver a New England Champion wrestler in just his third year running the program (A.J. Hunte, ’06), that we’d lead our team to its first winning record and first defeat of our rival Newton North in a decade a year later, then a playoff run, eventually becoming a conference and state powerhouse program. He didn’t know the school would be forced to swap our rickety van for a full-sized bus as he massively expanded the program. Coach would become most proud of the vaunted annual “Warrior Duals,” a unique team tournament hosted at Brookline High School, that he launched our junior year, cementing the town as a wrestling powerhouse.

Coach Carver also didn’t know how the grit I’d developed through this journey would later pay off big and small, when I fought to rebuild my career with grueling door-to-door fundraising, survive long-haul political campaigns, or start my own Political Action Committee, or learned years later through painful failures how to snowboard. He did not know how teaching me to build possibilities for myself would help me achieve goals I once thought impossible, like living abroad, working in Congress, or getting accepted to Georgetown’s MBA program – all because I once thought winning a wrestling match was impossible, but manifested it anyway, by enduring.

All Coach Carver knew when he woke up on February 4th, 2004, was what he taught us – hard work pays off, and champions are built, not born.

It seems so trivial to credit all these achievements to a high school sporting event. High School sports are not real life. To well-developed adults, they don’t matter much beyond their function as community events, usually around their own kids. But they mean a lot more to our young people. Sports change lives. They provide a fair, structured outlet for directing boundless energy toward productive futures, through community, teamwork, optimism, hard work, perseverance, and sportsmanship. And our young people eventually become all of us. I experienced all this through my grueling freshman wrestling season, in ways that have paid off countlessly these last twenty years. As I told Coach Carver a few years ago, there is not a week that goes by that I’m not thankful for what wrestling gave me.

Sports provide a redemption from the past, a refuge for the present, and opportunities for the future. When the referee raised my hand for real, I felt it all at once. And no one built it for me. I did it myself, through the yin and yang of wrestling.

That’s why every February 4th, I take a moment to remember the day when I figured out how to win. It was the day I took control of my own destiny, through the power of the greatest sport.

Thank you for reading. Send feedback to gregorynasif at gmail dot com.