Dissenting 101 was this writer’s sophomore thesis at the University of Maryland. In addition to a senior thesis, sophomore history majors at the UMD are also expected to produce an extensive paper of individual research.

In this paper, the nationwide student rebellion of the late 1960s and early 1970s is investigated at the University of Maryland, with an eye toward understanding the motives and beliefs of the many student protestors. This paper was submitted to UMD’s Janus Journal, which publishes ten undergraduate essays each year. The essay was accepted and published in Janus Journal for the 2010-2011 school year.

______________________________________________________________________________

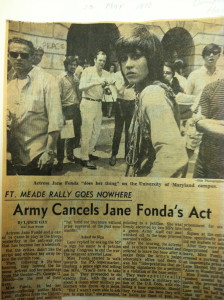

This is a reprint of a previous production by Gregory A Nasif. The pictures are iPhotos taken from cutouts of their newspapers, and are the copyrighted materials of those respective papers (cited above). They were presented at the 2011 Janus Journal Reception with the paper, but were not included in the original. If you would like to contact the writer, please email gregorynasif@gmail.com

Dissenting 101

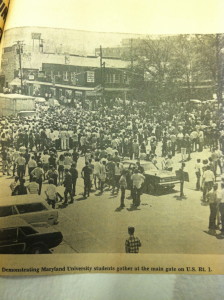

On April 30th, 1970, President Richard M. Nixon announced that the U.S. military had expanded the Vietnam War by invading the neighboring nation of Cambodia. With the war already enormously unpopular, the invasion sparked a colossal backlash in the United States, particularly among college students. The National Guard’s shooting deaths of four students at Kent State University during a protest severely exacerbated the mayhem. Students began striking all across the nation, and the University of Maryland was no exception. Once considered a conservative campus, the school experienced a massive radical upheaval, with students ransacking offices, blockading the nearby Route 1, and even trying to burn down the University Administration Building.[1] The disturbances persisted through 1972. The students were primarily protesting the Vietnam War, but other issues played a factor, such as the dismissal of two popular teachers, Civil Rights issues, grading policies, and in loco parentis, which is a school’s tendency to act as a parent for students living on campus.[2] Despite the diversity of the ideologies of the protests, the disturbances in College Park in the early 1970s were primarily rooted in the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

No students were present to witness this entire transformation, as the Civil Rights Movement developed some two decades before the school upheaval. However, University President Wilson Homer Elkins was there for the entire period, and his knowledge is therefore invaluable. Having witnessed the entire movement firsthand, Elkins may understand more about it than anyone else, even attributing it to his wife’s premature death in 1971.[3] Elkins acknowledged the trends and influences in the movements, but his inability to empathize with the students hampered his understanding of their meaning.

One of Elkins’s main concerns of the upheaval was the determination of the students to politicize the university – they wanted the school to take stands on certain issues, something Elkins showed his reluctance to do, stating “A university would not be a place for the free exchange of ideas, however, if one particular view, say the majority view, became the official policy of the institution.”[4] Elkins certainly lived up to this standard during the protests by taking no position on the Vietnam War. The University, against the wishes of the students, maintained its stock in corporations that dealt in defense contracts, and despite numerous protests, continued its Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program. However, Elkins was unable to maintain neutrality on the Civil Rights matter, for it was an on-campus issue that he had direct control over. There was no impartial stance for him to take.

“Students fly U.S. flag upside down as a distress signal at entrance of University o fMaryland [sic]” is the original caption. In the article, other students reverse this decision and return the flag to proper staff.

“State police use tear gas to push back demonstrators at Maryland University.” This is the southern Rt. 1 entrance to UMD. At the time, the vast majority of students lived in the dorms in that area.

The Civil Rights movement brought a new face to American dissent, beginning with a fresh supply of radicals. Most notable are the Black Panthers, a far-left black political party that sought to end not only the social discrimination of blacks, but also the economic oppression and forced military service they (among others) endured. Despite their often provocative rhetoric, they reflected a wider view – that African-Americans were fighting for freedom in another country when they weren’t even free in the United States. Possibly the most famous Civil Rights activist to hold this outlook was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., himself. Indeed, King’s popularity rapidly faded for holding this view, and his relationship with President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was escalating the war, soured. In 1967, he delivered a famous speech entitled “Beyond Vietnam,” criticizing the United States government for exploiting third world countries, focusing on fighting wars instead of poverty, and for sending African-Americans to fight for freedoms of other people when they themselves were not free.[11] Famous, or infamous, for his stubborn refusal to back down, this cost King a lot of support, prompting the Washington Post to state that King had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people.”[12] Despite the ultimate decline in the Civil Rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr.’s attempt to unite the movements made him a martyr of both crusades upon his assassination. The effects of his demise were intelligently outlined by Dr. Gregory Dunkel, a university alumnus who helped organize numerous demonstrations and was banned from campus within the first month of the uprising.[13] Martin Luther King Jr. and Gregory Dunkel, one the Civil Rights Activist turned Vietnam War protester, the other the opposite, both saw the common purposes of the Civil Rights movement and the anti-war movements, and the promise in a connection between the two.

More intelligent than his position as head of the radical Maryland mob might imply, Dunkel was among the few radicals to truly understand the nature of the times, and wrote an articulate paper in October of 1970 describing them. Wanting to help weld the movements, Dunkel outlines where the campaigns were, and where they were going. He marks racism between blacks and whites as “one of the strongest tools our enemies use to divide us,” and acknowledges that “Every black person in this country, no matter what his position, is subject to racist oppression.” Dunkel most descriptively explains the past failures of whites to help blacks, and how the connection between the two movements can strengthen them both, with this paragraph:

“In their concern about the oppression of the Vietnamese and in their anger over that barbarous war, white students ignored the similar kinds of oppression coming down on black people in front of their noses and failed to see that in order to fight one kind of oppression you have to fight the other. At times, white students failed to support or even opposed demands for black studies programs, black dormitories and open admission because these demands were ‘reformist” or “divisive.” Such students failed to realize that any nation, including national minorities in America, and any people has a right to control its own culture and education and institutions.”[14]

It is eerily similar to a famous quote by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”[15] By uniting the “radical” fronts, Dunkel and King believed they could create a stronger campaign. They believed in collectivism – that the whole of the movement would be greater than the sum of its parts.

Aside from providing human rights to blacks, the Civil Rights movement’s greatest asset was how it was conducted; despite the violence that accompanied it, the protesters led a campaign of peace. One of the most prominent forms of protest popularized during the Civil Rights Movement was civil disobedience, the most celebrated instance being Rosa Parks’s refusal to stand from a white-only bus seat in 1955. Civil Disobedience is the act of intentionally breaking the law and accepting the punishment to make a political or legal statement about that law. More examples of it include the “freedom riders,” when Black Civil Rights activists rode interstate buses to segregated states to challenge those states’ segregation laws, or sit-ins at white-only restaurants. This tactic was swiftly adapted by the protesters of other causes in the late 1960s and early 1970s, especially at the University of Maryland in College Park. Most of these students were new to the dissenting scene, and they took heed from an experienced group. Civil Rights activists had already been protesting for two decades, and, naturally, had a lot to offer.

In March of 1970, students kicked off a turbulent spring of disturbances by protesting the school’s refusal to grant tenure to two popular professors.[16] The demonstration quickly escalated, and students subsequently stormed and took over the school’s Skinner Building, barricading themselves inside for hours. When the police finally intervened to remove the students, they sat on the floor singing America the Beautiful at the instruction of Reverend David J. Loomis (later given a short prison sentence for his role in the takeover), as a peaceful show of civil disobedience.[17] This scene would repeat itself again and again, as students took these events further and further. The school ROTC offices in the Armory were frequently raided, and one night in May 1970, a few radicals even tried to burn down the school’s South Administration Building, before being thwarted by other students.[18] Sit-ins at the ROTC offices continued, returning in 1971. Radical activists began hosting “Civil Disobedience Training Sessions” in Washington, D.C., organizing another ROTC sit-in in the Armory on April 29th, 1971, marking the one year anniversary of President Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia.[19] The activists were planning on honoring May Day, or May 1st, with “a general moratorium on business as usual” and demonstrations and civil disobedience at the Justice Department in Washington. On the whole, done peacefully in most cases, though violently in a few, Civil Disobedience was successfully adopted into the Maryland Student rebellion of the early 1970s from the Civil Rights movement.

One of the most iconic signs of the African-American struggle was the clenched fist, also known as the “Black Power” symbol. However, as the Civil Rights movement continued to influence the anti-war protests, the power symbol quickly began to encompass the student rebellion as a whole. At school protests around the nation, clenched fists became the official sign of dissent and counterculture.[20] Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post said that by early May, the clenched fist symbol with “a strike” under it had become somewhat of a mainstream image on American college campuses.[21] The Symbol had changed from a sign of Black Power to one of pure resistance. The culmination of this was at the University of Maryland Commencement on June 6th, 1970, when hundreds of graduating students decided to adorn the back of their black gowns with cardboard cutouts of a peace symbol, surrounding a clenched fist.[22] Enduring heckles and boos of conservative parents and faculty, graduating student Stuart J. Robinson told the crowd before him “You have learned how irrational rhetoric and insensitivity to felt needs can produce confrontation and violence. You have tasted the bitter taste of repression,” referring, perhaps, to the backlash caused not only by decades of ‘oppression’ of students, but to the backlash of centuries of oppression of blacks.[23] The two symbols, one of peace, the other of equality, over a black gown, are an incredible reminder of the unity of the two movements. The clenched fist was another product of the Civil Rights movement that was successfully adopted by the Maryland student rebellion of the early 1970s.

Those who booed Stuart J. Robinson at his commencement were a part of a larger constituency. It is understandably hard to hold one’s temper when students are chanting at you, “Pigs, pigs, fascist pigs!”[24] As the national student rebellion grew, a conservative, reactionary countermovement quickly gained steam, made up of predominantly older generations. An angry bunch, they were even faster to group the radical campaigns together as one assembly of disobedient punks than the causes themselves. Upon learning of the university’s allegedly amnesty-granting response to the disturbances in the spring of 1970, the Maryland State American Legion Convention passed a resolution calling for the state to pass legislation immediately expelling students taking part in tumultuous demonstrations, and withholding funding from colleges that fail to do so. Even at the trials of 75 students arrested for disturbances, there were allegations of discrimination against the students based on their attire, hair style, and even skin color.[25] In October of 1970, the conservative student group “Young Americans For Freedom,” alleged that the mandatory $18-a-student fee paid to the University for joining clubs was funding the enormous disturbances, specifically citing the Black Student Union and the Vietnam Moratorium Committee in an angry letter to the Maryland State Attorney General, Francis B. Burch.[26]

“Maryland National Guardsmen, bayonets fixed, bar students from College Park Administration building yesterday.”

In their fury towards the demonstrating students, the conservatives often didn’t bother to separate the radicals or their varying ideological goals, viewing them as the larger throng they were slowly becoming. The University acted similarly in trying to appease the rampaging students. In August 1969, the University Administration simultaneously established a judiciary system that was controlled predominantly by students, banned classified military research, and pledged to admit more blacks in an effort to pacify an irate student body, doing so by appealing to both anti-war, in loco parentis, and Civil Rights sentiment.[27] In 1970, the University also created the position of a Human Relations Officer, who would serve under the Chancellor of the College Park campus.[28] The Officer was charged with the responsibility of monitoring student welfare pertaining primarily to race, but would include any other services resulting from stress, fear, or anxiety among the student body. The University of Maryland had acknowledged the increased strength of the uniting movements, and reacted accordingly.

!["[cut]N EFFIGY - Student demonstrators drag uniformed dummy to administration building, where it was burned." The dummy reads "US MILITARY MACHINE."](https://gregnasif.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/IMG_0085-300x224.jpg)

“[cut]N EFFIGY – Student demonstrators drag uniformed dummy to administration building, where it was burned.” The dummy reads “US MILITARY MACHINE.”

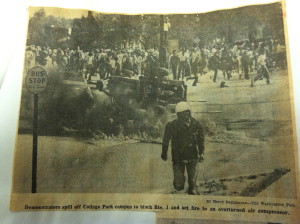

“Demonstrators spill off College Park campus to block Rte. 1 and set fire to an overturned air compressor.”

They were planning what they termed the “People’s Constitutional Convention,” and on September 24th, 1970, Davis stood in front of 600 students and urged them to book the Cole Field House for the Convention “by any means necessary.”[33] The students, Panthers, and Davis wanted to write and frame a new Constitution that they felt would better serve minorities in a purportedly racist and oppressive country. Throughout a brief lull in the demonstrations during the winter of 1970-1971, radicals voiced their disappointment with the calm, complaining that students were not actively working against racism on campus and the war in Vietnam.[34] In fact, before the end of May 1970, it had already been documented that blacks were significantly more against the war than whites, and that the dominance of whites in the Maryland protests were a result of nothing more than the dominance of whites at the school in general.[35] Many were upset that too many Blacks were sent to Vietnam immediately after graduating from high school or college.[36] Indeed, the movements had become one, indicative of the fact that the protests were rooted in dissent surrounding the Civil Rights movement.

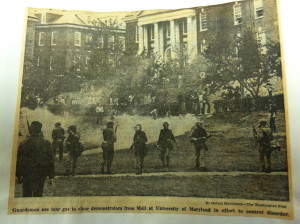

“Guardsmen use tear gas to clear demonstrators from Mall at University of Maryland in effort to control disorder.”

In addition to protesting the Vietnam War and Civil Rights issues, students were also protesting in loco parentis, the practice of the school playing the role of the parents for kids away from home.[37] Among many rules the students found oppressive, boys and girls had to adhere to curfews and lived in separate dorms.[38] Elkins stated that he believed this uprising was rooted in the Civil Rights movement.

“I think it grew out of the Civil Rights movement. The Civil Rights movement was for the rights of the people, and the students were expressing what they thought were their rights as individuals. I think the protest came at this time because it was an outgrowth of Civil Rights.”

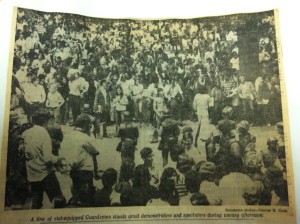

“A line of riot-equipped Guardsmen stands amid demonstrators and spectators during uneasy afternoon.”

Elkins believed it was a rolling process as the students developed a larger sense of personal freedom. Perhaps the peak of the in loco parentis protests was when the University faculty voted to retain the right to academically punish students for missing classes during the disturbances in the Spring of 1970.[39] After that announcement, students immediately poured back onto Route 1, blocking traffic, battling national guardsmen, and destroying property. President Elkins stated that he thought the in loco parentis movement and anti-war movements were completely independent of one another, but he never considered that they were both rooted in the same ideals.[40] The Students were fed up with feeling oppressed and exploited for the country’s economic and military benefit. They wanted freedom, and whether that freedom came in the form of being judged independently of the color of their skin, living free lives when they turned 18, or not being sent to die in an unjust war, they were scared and angry enough to take drastic measures for it.

Though this generation had a tumultuous college life, their childhood was a far greater time. The United States of America enjoyed enormous growth, prosperity, and optimism in the years following the Second World War. These good feelings gave way to the Baby Boom, an enormous generation that would grow up to see all of that positive energy unravel. In a sad, yet tumultuous, almost exciting moment in American history, our nation tore itself apart, from beatings of black women on the “freedom rider” buses, to construction workers fighting students in New York, to Senator Strom Thurmond deliberating on the Senate floor for nearly 25 hours, to suffocating students bursting out of a gassed Montgomery Hall to vomit. Clearly, anger was America’s newest abundant resource.

When we get angry, we tend to lose track of our emotions and our actions, which is why we so often act irrationally. Thus, when examining a period of such high tempers, it is very hard to pick the pieces apart. Anger is also contagious, and can spread across constituencies, political parties, religions, and all kinds of other denominations. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, it spilled onto the campus of the University of Maryland, College Park, driving Civil Rights, student rights, and anti-war protests.

The Black Student Union was perhaps the first to resort to drastic action.[41] The escalation of an already unpopular war by an already unpopular president in 1970 lead to a dramatic increase in what was now the hottest idea for American protest – getting attention, usually by destroying things. The rebellion would accompany some of the basic tenets of the Civil Rights movement, like symbols and civil disobedience, but more often than not centered on destruction and disruption. As these issues unfolded, and as student rage grew, they clenched their fists, set their minds, and demanded everything they felt they deserved – no longer patiently awaiting the healing power of time, creating the in loco parentis protests to cap off what would culminate in three years of bloody, garbled carnage. All of this from the drive for equality for blacks – the disturbances at the University of Maryland in the early 1970s were primarily rooted in the Civil Rights movement of the previous two decades. Let us hope, in the future, that this is not the cost of freedom. The University of Maryland may just depend on it.

–

–

–

Works Cited

Dunkel, Gregory. “Friends and Foes,” Campus Unrest, Aug. 1970 – Dec. 1970. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Archives, Maryland Room, R. Lee Hornbake Library, 1970.

Elkins, Wilson H. Forty Years as a College President, ed. By George H. Callcott. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Press, 1981.

Farrar, Hayward “Woody.” “Prying the Door Farther Open: A Memoir of Black Student Protest at the University of Maryland, College Park, 1966 – 1970,” in Higher Education and the Civil Rights Movement: White Supremacy, Black Southerners, and College Campuses, ed. by Peter Wallenstein. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2008.

Kalb, Barry. “The Scenes Are Changing: Hot Issues Abound at Area Colleges,” Washington Evening Star, April 20, 1970.

King, Dr. Martin Luther, Jr. “Beyond Vietnam,” April 4, 1967, Hartford Web Publishing, http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/058.html (accessed April 30, 2009).

King, Dr. Martin Luther, Jr. “A Letter from Birmingham Jail (April 16, 1963),” in Voices of Dissent, ed. by William F. Grover and Joseph G. Peschek. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008.

Lawson, Steven F., Charles M. Payne, and James T. Patterson. Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945 – 1968. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006).

Sun Staff Correspondent. “Campus Disruption Perils Cited: Commencement Speech at UM is Warning About ‘Backlash,’” Baltimore Sun, June 7, 1970.

[1] Peter Osnos, “Activism Spreads at U. of Md.,” Washington Post, December 14, 1969; Hayward “Woody” Farrar, “Prying the Door Farther Open: A Memoir of Black Student Protest at the University of Maryland, College Park, 1966-1970,” in Higher Education and the Civil Rights Movement: White Supremacy, Black Southerners, and College Campuses, edited by Peter Wallenstein (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2008), 137.

[2] Barry Kalb, “The Scenes Are Changing: Hot Issues Abound at Area Colleges,” Washington Evening Star, April 20, 1970; “1,500 At UM Storm Onto U.S. 1 Again: Guard, Police Sent in After Grading Vote Sets Off Outburst,” Baltimore Sun, May 15, 1970; Wilson H. Elkins, “Forty Years as a College President,” ed. George H. Callcott (College park, MD: University of Maryland Press, 1981), 125.

[3] Elkins, 133.

[4] Ibid., 123.

[5] Ibid., 158; “Students Air Gripes In 2-Hour Talks With Head Of Md. U.,” Washington Post, April 1970.

[6] Elkins, 158.

[7] “Students Air Gripes;” Douglas Watson, “Maryland U. Protest Gets Lee Support,” Washington Post, October 10, 1971; Goo; “Md. U. Takeover Blocked;” Farrar, 149-150.

[8] Farrar, 162.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 147; Elkins 133; Rowland, “Mandel’s Md. U. Stand a Vote-Getter,” Washington Sunday Star, May 17, 1970; “UM Semester Ending Quietly In Contrast To May’s Unrest,” Baltimore Evening Sun, January 1, 1971.

[11] Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Hartford Web Publishing, “Beyond Vietnam (4 April 1967),” http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/058.html (accessed April 30, 2009).

[12] Charles M. Payne, James T. Patterson, and Steven F. Lawson, Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), 148.

[13] Susan Karat MacAdams, “35th Anniversary Memoir from a Route One Brigadonna,” University of Maryland Activists Reunite!, http://www.route-one.org/students/35th-anniversary-memoir-from-a-route-one-brigadonna.html (accessed April 30, 2009); Dr. Gregory Dunkel, University of Maryland Archives, R. Lee Hornbake Library, “Campus Unrest,” October 1970 (accessed April 2, 2009); Alvin P. Sanoff, “Elkins Sites A Hard Core: Tells Regents UM Is Not ‘Geared For Violence,’” Baltimore Sun, May 16, 1970; “Md. U. Takeover Blocked,” Washington Evening Star, April 24, 1969.

[14] Dunkel.

[15] Martin Luther King Jr., “A Letter From Birmingham Jail,” in Voices of Dissent, ed. by William F. Grover and Joseph G. Peschek, (New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008), 317.

[16] Kalb.

[17] Jonathan Rodeheffer, “76 Convicted Of Trespass in UM Sit-In,” Baltimore Sun, July 3, 1970; “County Court Sentences 75 For Protest at Maryland U.,” Washington Evening Star, August 11, 1970.

[18] Love; AP, “Stirred by Kent State Fatalities, Students Across Nation,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 5, 1970; “UM Chancellor Disperses Sit-In: Bishop Tells ROTC Protest, ‘You’ve Made Your Point,’” Baltimore Sun, October 6, 1970; Lance Gay and Walter Taylor, “Violence Erupts Again At Md. U.: Guard, Police Quell Disorder,” Washington Evening Star, May 15, 1970; Chuck Petrowski, “About 80 Jam into ROTC Office,” The Diamondback, April 30, 1971

[19] Petrowski.

[20] “Mandel Declares Md. U. Emergency,” Washington Post, May 5, 1970, (Post Staff Writer).

[21] Carl Bernstein, Washington Post, May 7, 1970.

[22] “Campus Disruption Perils Cited: Commencement Speech at UM Is Warning About ‘Backlash,’” Baltimore Sun, June 7, 1970 (Sun Staff Correspondent).

[23] Ibid.

[24] Thomas Love, “Tear Gas Quells Md. U. Outburst After 13 Hours,” Washington Evening Star, May 2, 1970.

[25] C. Mason White, “UM Sit-In Convictions Upheld on Appeal: State Court Rules in Case of 59 Seized Last Year,” Baltimore Sun, June 8, 1971.

[26] “Rightist Group At UM Ties Student Fees To Disorders,” Baltimore Sun, October 8, 1970 (by Staff Correspondence).

[27] Melvin Goo, “Area Schools Plan Series of Reforms,” Washington Post, August 25th, 1969.

[28] “Maryland University: Senate (C.P.) Minutes, Oct. 1969-Feb. 1970,” University of Maryland Archives, R. Lee Hornbake Library, (accessed April 24, 2009).

[29] “U. of M. Calm as Curfew is Enforce: Mandel Vows to Back 300 Guardsmen with 9,700 More,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 15, 1970 (by a Sun Staff Correspondent).

[30] Lawrence Meyer, “Maryland U. Disorders Mold Student-Faculty Alliance,” Washington Post, May 25, 1970.

[31] William Greider, John Hanrahan, David Boldt, Richard M. Cohen, multiple articles, Washington Post, July 5, 1970.

[32] James B. Rowland, “Elkins Asks Court on Md. U. Violence,” Washington Evening Star, June 13, 1970.

[33] “CONVENTION OF RADICALS URGED AT UM: Panthers, Rennie Davis Meet With Students; Officials Surprised,” September 25, 1970 (by a Sun Staff Correspondent).

[34]Lance Gay, “Md. U. Unrest Turns to Communication,” Washington Evening Star, December 21, 1970.

[35] Carl Davidson, “What do the Protests Mean?” The Guardian, May 23, 1970.

[36] “2 Blacks Killed in Protest,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 15, 1970 (Sun Staff Correspondent).

[37] Elkins 125; Dunkel.

[38] Elkins 126.

[39] Rowland, “1,500 At UM,” Elkins 126-128.

[40] Elkins 132.

[41] Farrar 140-156.

_______________________________________________________________________

This is a reprint of a previous production by Gregory A Nasif. The pictures are iPhotos taken from cutouts of their newspapers, and are the copyrighted materials of those respective papers (cited above). They were presented at the 2011 Janus Journal Reception with the paper, but were not included in the original. If you would like to contact the writer, please email gregorynasif@gmail.com

!["Police use tear gas and dog [sic] to scatter students at the University of Maryland yesterday."](https://gregnasif.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/IMG_0086-300x224.jpg)