I teach in many schools.

Specifically, Japanese private kindergartens. Young kids rarely learn anything their usual Japanese Sensei doesn’t already know. However, Japanese school officials acknowledge that many adults are far too timid with gaijin (foreigners). They believe exposing young children to foreigners will help them embrace English learning throughout their lives.

Since I am legally forbidden from sharing pictures of my students, here is a picture of another Japanese Kindergarten class from the Wall Street Journal.

The schools I teach in are spread throughout the metropolitan area of Osaka, Japan’s second largest city. In Japan, Kindergarten includes a compulsory form of what the western world understands as optional “Pre-K,” and has three levels: the three to four-year-old “Nensho,” the four to five-year-old “Nenchu,” and the five to six-year-old “Nencho.”

Starting this job was frightening for me, although frightening was an improvement. Thanks to some chats I had with encouraging people at the right time, I felt reassured that I was capable of fulfilling my requirements. No longer quite petrified, I was still confused by the young children and nervous about making mistakes. I didn’t understand them.

It was the unknown and I was scared. Having conquered the last transition, I was ready to try.

The job began with a period of sponge learning. In lieu of training, which I was unable to attend while moving from Kyoto to Osaka, I spent a few weeks watching lessons taught by more experienced teachers. Trying to suspend odd impressions, I absorbed their styles, their mannerisms, and their confidence.

Some of the company’s experienced teachers were normally quiet and shy, but dropping them amongst a number of young children brought their humanity to life. Among this group, the teachers took advantage of their quiet demeanors to tease the children with deadpan humor. It was actually intriguing – making children laugh suddenly became kind of an easy skill to understand. It explained to me why Paul Rudd started as a Bar Mitzfah DJ.

Some teachers simplified their English to basic, loud directions. Others used Japanese, which for me was certainly not an option, at least in the beginning. A few teachers employed English in a Japanese accent. I definitely wasn’t interested in that.

When finally it was my turn to teach, copying was the easy way to start. I mimicked the structure of some teachers, the games of others, and the mannerisms of yet more, synthesizing my own teaching method. I stole many more ideas and strategies from the many teachers I watched – at their behest and encouragement. Finally, I took a select few skills from my old job. The sponge was soaked.

The training wheels were removed gracefully, as observing teachers would step in when I asked to provide alternative activities. In a time of such radical change in my life I was very open to criticism and learned quickly. Nonetheless, everything came from the other teachers. I was still acting out of some sort of fear of the young students. It felt reassuring to synthesize my own style, but I sought my own inspiration.

With the 50-minute afternoon lessons under control, I next learned about our morning lessons, when regular school is in session. Japanese kindergarten classes typically consist of 25-40 students per classroom. And for 20-30 minute periods, they are entirely mine. Far more energetic and fast-paced, these lessons could be more accurately described as fascist rallies.

For one year, I will go to a different, designated school each morning of the week. By the second time I arrive at one of these schools, I am heralded by my name being screamed over and over. As soon as I appear in on open school grounds, “GREG SENSEI!” rings into my ears. Whether it’s in greeting, to acknowledge my presence to the other students, or even to acknowledge my presence to themselves, students feel the need to scream at my arrival. In saying my name, I note how they already have better pronunciation than the Japanese adults I used to teach, who often got stuck on syllabric sounds and called me “Guregu.” And I note how dearly happy most of them are to see me.

When the lesson begins, the students are seated facing me in a horseshoe, and there is a sort of righteous focus of energy on me. Anything I do with enough force and rhythm is immediately imitated by all the students. They scream what I tell them to scream. They hop on one leg when I tell them to hop on one leg, shouting “Hop! Hop! Hop!” or more likely just “Ah! Ah! Ah!” This attitude makes it easy to organize games, to scare the children, and to make them repeat new vocabulary. With complete control I have naturally begun and ended most lessons with a salute. Hail Greg Sensei!

Scaring the children lightheartedly is integral to making the lesson thrilling and exciting for them. Throughout both types of lessons the principle tools for this are “boo-boo cards,” or flashcards designated only to getting a rise out of the children. Sometimes they are an intricate part of a game, triggering a reset (think when a board game “pops” and all the pieces fly everywhere). Sometimes they are just snuck into regular vocabulary drilling: “It’s a circle! (shift) It’s a square! (shift) AAAAAH GORILLA!!”

The gorilla is popular, because it’s a funny animal. But my favorite is just a picture of Godzilla.

Making Japanese children run away screaming “GO–JIRA!!!” is a dream-come-true.

Delivery is just as important. In working on my composure when presenting a horrifying card, from calmly not realizing what I’ve shown, to shock, to sharing the terror with the students, I found myself, for the first time in this job, really having fun teaching. Sometimes I scream louder than any of them, but when in doubt, they’ll always mirror my reaction. Every week I make this feature of the class more exciting, as the students seemingly never get tired of my “genuine” surprise when Godzilla, or a gorilla, or a monkey, or underpants, or a shark, or Hungry Sensei find their way into my teaching materials.

But the pinnacle of my experience in Japanese schools is the 30-minute lunch I share with four, five, and six-year old Japanese students. Part of the inclusive program at a school where I teach all day once a week (as opposed to most schools which are only morning or afternoon), these lunches have become the strangest and funniest moments yet of my short time in Japan.

–

Lunch

The lunches I sit with the students can not be described with any metaphor.

Still a rookie in teaching children, still a beginner in the Japanese language, and for what it’s worth, a misplaced, gangly 26-year-old with a huge appetite, I sit on a tiny chair at a tiny table with thirty tiny children, eating a tiny lunch.

In true Japanese form, I try desperately to fit in as normally as possible. Immature as I may be, there is one insurmountable hurdle.

“Greg Sensei, ひるごはんがおうきいです!” says a student, pointing the lunch provided for me.

“What?”

“おれのみて!” she insists, now pointing at her own lunchbox.

In a few seconds, all thirty students yell “Greg Sensei, oreno mité! (look at mine!)” and show me their colorful lunchboxes and chopstick cases. Each is themed with a popular Japanese cartoon, the most popular being “Yo-Kai Watch.” But I can’t tell the difference between that, Anpanman, some strange anime versions of Transformers or Power Rangers, or most any other of the cartoons featured. In fact, I only recognize one.

“Pokemon!” I scream, pointing at one girl’s ancient lunchbox. She lights up. “Pokemon?” repeat the children, bewildered. Instantly, I am old and uncool.

But before the students can all make fun of Greg Sensei’s knowledge of Pokemon, Japanese Sensei starts playing on the piano, because every Japanese Sensei is an expert pianist. The children scatter like it’s a bombing raid, scrambling for their chairs, where they sit and pretend to sleep through Sensei’s soothing notes. Yet they all peek through half-closed eyes. They peek at Greg Sensei, who hilariously has no idea what to do.

The tone of the music kicks up. The kids ‘wake up,’ clap and dance, chanting something in Japanese, looking at me with curious smiles. I am not sure if they are laughing with me or at me. Their hands go up, down, around, and twist. It’s like a long and exciting story.

The terrifying, ritualistic chant ends with several phrases I recognize as the Japanese “bon appetite” and different forms of “thank you.” I’ve just witnessed the extended form of saying grace in Japan. It took over two minutes.

The eating begins. And the students start talking to me, the only way they know how.

“Greg Sensei! (Speaking Japanese)”

“English please.”

“犬あります.”

“Uhhhh”

“僕の犬は面白い。猫を家中追いかけている! ご褒美を食べるけれど、僕のご飯も食べる。鶏肉がとても好き。グレッグ先生も、鶏肉が好きだよね。ある時僕の犬は猫を追いかけた。彼は猫を食べたかったんだ。彼はいえじゅう猫を追い回して、そして植物を割った。ハルはチキンじゃないから僕の犬はきっと猫とチキンが好きなんだ。”

“English please!” I repeat, with less confidence.

For the Japanese Sensei at another table, there is little reaction to my struggles and bewilderment. Trained as all Japanese are in the art of concealing emotion and maintaining discipline, I wonder if she is struggling with repressed amusement at my predicament. As I have lunch with four different senseis in a month, my curiosity slowly shifts to wondering why all Japanese Senseis seem to be so beautiful, so sweet, so gentle… kind… lov–

“Tomato!” screams a student, evidently for the third time. Was that English?

“Yes, tomato!” I encourage her, seeing her hold the same. “Sushi!” I added, pointing at some seaweed wrapped around rice in her small lunchbox.

“Onigiri?” she asks, confused. Then, noticing something else in her high organized and neatly packed lunchbox, so perfectly representative of Japan’s highly organized and neatly packed society, she shrieks, “Mité!”

She raises in her arm a little jello cup the size of a bottle cap.

Not wanting to miss the chance to show me their favorite food item, the other 25 students pull out their little jello cup deserts too, and run over shouting “Oreno mité !” Vaguely I wonder if they were giving me this food, so I try to take one of the cups. There follows an immediate and tumultuous uproar, very much answering that question. The children are not going to give me their food today.

As the students sit down I eat half my lunch.

A girl sitting on my other side tells me a story about her nose. I only know this because she keeps pointing at it.

“Nose!” I say.

“え?”

Touching my nose I repeat, “nose!”

“はな?” she says. Correct.

Moving my finger down, I say, “mouth!”

She points to her ear. “Ear!” I say. Connection is made.

She points to her shoulder, her eye, her hair, and each time, I teach her a new word. She repeats the words, but not once does she smile. To her, I am a means to an end. I surmise this is the smartest girl in the class. Unfortunately she’s also lazy. She stops pointing to body parts and starts just saying them.

“うで” she says.

“English please,” I repeat, clearly forgetting the purpose of our interaction. Her eyebrows go up in judgment.

“うで!” she repeats. I stare blankly. She rolls her eyes and stops paying attention to me.

Finishing my tiny lunch well before all the uncoordinated children with their bellwether appetites and pitiful chopstick skills, I stand up and roam the room, delaying any food consumption within a five-foot perimeter as students stare at me, smile, and babble in Japanese. The first girl to finish her lunch runs up to me and asks me a question I don’t understand. Unsure of how to respond, I promptly pick her up, lift her to the sky, and put her down. Big mistake.

Within a couple minutes six students are laughing and fidgeting through a recycling line, each eagerly anticipating my lifting them safely into the sky. Tired as I am, the smiles on their faces hold a power over me. I can’t stop. The most I can do is make them say “up, please!”

After a few weeks of not speaking Japanese and pretending it was for the children’s benefit, I finally picked up enough vocabulary to hold extremely basic conversations with them. But the revelation of this skill had to be carefully calculated, for if the students found out how poor my Japanese skills were, they would inevitably use that knowledge against me. And so was my concern as lunches empty, and students retire to the walls of the classroom to pull out books.

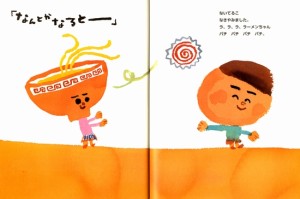

A quick observation reveals that these kids’ books are devoid of Kanji (Han Characters), and often have simple script next to pictures teaching animals, seasons, foods, etc. In the classroom my senses are heightened. More astutely aware of Japanese script with these books than I ever was outside the classroom, there arises a sudden, crucial, deep connection with the students. I’m not sure what it is at this point.

A cute little girl beckons me to read a book with her about a walking, talking bowl of ramen. So I read, out loud, revealing Japanese literacy for the first time. The young girl follows at an identical speed.

“ラ, ラ, ラ, ラーメンちゃん, バチ バチ バチ, どこへいきたいですか?”

“Ra, Ra, Ra, Rāmen-chan, bachi bachi bachi, doko e ikitai desuka?”

“ラ, ラ, ラ, ラーメンちゃん, バチ バチ バチ, ながいめんをみてください!”

“Ra, Ra, Ra, Rāmen-chan, bachi bachi bachi, nagai men o-mite kudasai!”

I don’t know if she reads as slowly as me because she wants to help me learn the script, or because she’s five years old. But I learn so many things in this moment. I learn that I’m not far behind these kids. They haven’t been in Japan much longer than I have, anyway. Conversely I realize that although more than five times their age, they still know more about Japan than I do.

Their honest and determined effort to speak Japanese to me has broken down mental barriers to learning Japanese, convincing me once and for all that it’s a real language, not jibberish designed to confuse me. In this moment I feel the weight of the culture in this children’s book, in the child reading it with me, and this room with so many others who know virtually nothing of any other society, as I knew so little about the world when I was their age.

And when I look up, I find all 25 of them, including the Japanese Sensei, staring at me in shock.

“Greg Sensei Nihongo shaberu! (Greg Sensei speaks Japanese!)”

Should I correct them? I wonder, as they start asking me a flurry of Japanese questions. I understand nothing as usual. But my heart is warmed, and I bask in the false glory.

The Transition Comes Full Circle

Clearly things are going swimmingly at this school. As a friend foretold would happen months before, I’m “treated like a rockstar.”

But of course teaching at seven schools, I get a mixed bag. Some schools have slightly more violent children, bizarrely obsessed with punching me in sensitive areas as some form of greeting.

Others have hilariously absorbent children, who have taken to screaming “Oh my God!” and “Oh no!” Hopefully this doesn’t stand as a testament to my temperament in the classroom.

Interestingly, this absorbent quality seems to happen more at schools in poorer areas. Something a respected superior in the industry once said to me comes up: Poor kids learn faster.

These schools in poorer areas may have scrappier, more excitable, English-loving children. At these schools the children adjust quickly to me as their teacher, developing dependable loyalty and affection for me. But these schools also tend to have stranger management.

It was going to these schools that helped illuminate the completion of a long transition.

Dealing with children professionally, alone, for the first time, I counted a lot on help from Japanese staff. Talking to schools, disciplining children, translating everything from forms to the complex nuances of children, the Japanese staff members were captains steering me out of troubled waters. And when the captains lose confidence, the water suddenly seems a lot choppier.

Japanese business is weird. I don’t want to go into it too much, but witnessing my bosses being bullied by bizarre school officials is an odd experience. Think Evil Michael Scott.

One high-ranking school official in particular conducted a reign of terror over the phone to our bosses for some time, making all kinds of demands, cursing, insulting, and requesting arbitrary, useless shows of devotion from all of us (like writing resumes by hand). After two months teaching without hiccups at his school and without appearance from him, this mysterious tele-nazi surfaced in the flesh, emerging from the office as we arrived at the school, and chose to replace our prep time with his own impromptu interview with us, the two Native English-speaking teachers.

Although I wasn’t afraid for myself personally, I was not very experienced with formal business meetings with Japanese people, and I was conscious of what was at stake for my new employers, whom I like very much. Once again, it was the unknown and I was scared. The man questioned us on every aspect of our lives.

Meanwhile the minutes ticked away. I was scheduled to begin teaching three-year-olds – a highly delicate operation – in twenty minutes… in fifteen minutes… in ten minutes… in five minutes…

Finally with two minutes to go we informed him we’d be happy to answer any more questions the next time we came in, or if he called our office. It took us another few minutes to get away regardless, following Japanese business protocols. Late for our class, we sprinted up the stairs. I was in a panic. How could I possibly handle a class of three-year-olds without any preparation?

The moment I entered the room, everything changed – or things that had already changed became immediately apparent.

“Woah!” I shouted, acting surprised to see them, all seated in chairs laid out by the Japanese staff member. The children turned their heads, and burst into laughter. My appearance alone fully satisfied them. As I made a fifteen-minute gag out of removing teaching materials from my bag, looking at the smiles on their faces, forgetting my complete incapability to ever make an adult that happy, I reciprocated their amusement. I couldn’t have been more pleased or more relieved myself. No more crazy people, just pure teaching to pure learners. Children are just that much cooler to be around than adults.

Transition complete.

Champs. (photo source)

Thanks for reading.

@gregnasif

Excellent.