Surprises are big and small when you live abroad.

I am not sure how obvious this is to most people, but something that intrigued me about Japan is how everyone I encountered seemed to be able to read the Latin Alphabet. Japanese people appear to read Latin characters, or in Japanese, “Romaji” (when he visited, my brother most eloquently asked “when you say Roman characters, you mean English, right?”) nearly on pace with native English speakers.

Initially I thought this was because I was being trained as an English teacher. Only encountering highly proficient English students, of course one would think they all read the language without difficulty. Then I noticed, in the building where I worked, all the McDonald’s workers could read my written coffee requests. They even understood “medium,” which soon became “large” when I saw how tiny the portions were over here.

Perhaps international restaurants were training their workers to recognize key English words? I tested this theory on a waiter in a restaurant instead. After briefly attempting to ask the man for what I wanted, it became clear that he did not speak a word of English. So I wrote down “iced coffee.” And out of him came a quiet, nervous voice, quivering with such customary Japanese terror of imperfection: “Icu do cohee.” And soon an iced coffee was chilling my ungloved hand (note: it’s actually icu cohee).

Looking around I couldn’t fail to notice the widespread adoption of English words in advertising, on clothing, and in artwork. It seemed every normally educated person could read the Latin script in addition to the three scripts used in Japanese, even if what was written made little or no sense.

In November, I encountered one of Kyoto’s very few homeless men in yet another McDonald’s (I swear I don’t spend much time in them), and, out of boredom, engaged him in “conversation” during a two hour wait for the morning trains.

While the man mostly stammered and muttered to himself in Japanese, I searched for a conversation topic and asked about his hat. He instantly took it off and read the logo on it, in a slow, concentrated manner with furrowed eyebrows that suggested he was reading it for the first time: The Old Boys’ Club. When I merely nodded he began shouting it over and over. “Ze Oldu Boysu’ Clubu! Ze Oldu Boysu Clubu!”

Quite as amazing as the nationwide Roman literacy is its immaculate inscription, stemming from calligraphy practice in elementary school. I’ve taught between 100 and 150 students throughout this year, and I estimate I have better handwriting than three to five of them.

Nowhere was this better encapsulated than on Dejima Island in Nagasaki, where I also learned of Japan’s hilarious introduction to the wild animals of the tropics.

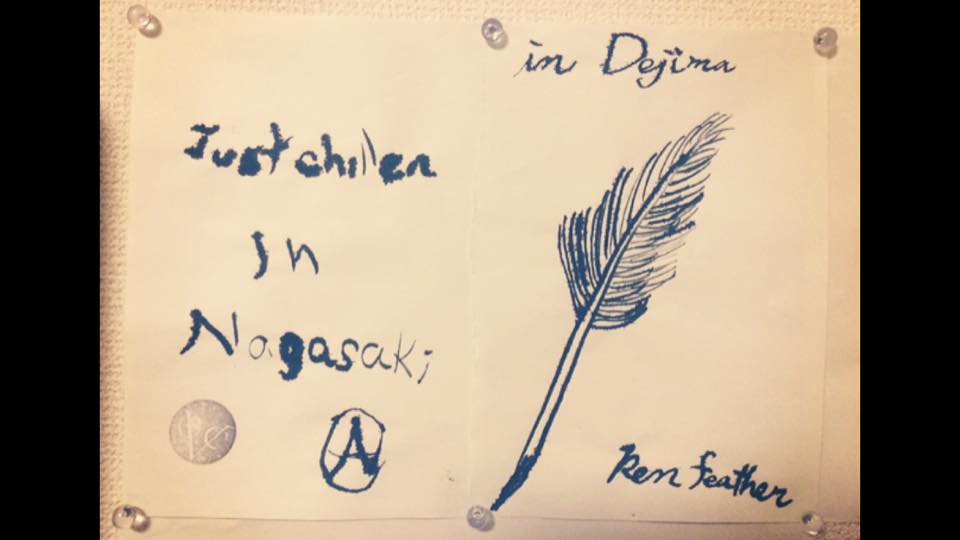

There, with my friend Miharu, in the open calligraphy room of the British-built “International Club,” we drew these two cards:

Here captured were the principal differences between English writing by my people and by Miharu’s people. While “chillen” is obviously not in the dictionary, it’s the phonetic sounding of a jargonistic word, hence it is the pinnacle of slang, which is itself the most difficult, impenetrable branch of linguistics – the citadel of a language. Yes, “Just chillen in Nagasaki” represents complete command of the English tongue. On the other hand, my handwriting is abominable. My elementary school teachers should be ashamed of themselves.

Miharu, meanwhile, wrote “pen feather.” Her feisty and determined effort to speak a language she doesn’t understand is part of the appeal of Japanese girls. You could laugh at them, but then you’d have to ask yourself, in how many languages can you say ‘quill?’ And then, you’d have to consider the other reason her artwork is on my wall: because it’s beautiful. She writes better and more smoothly with ink and a quill than I can with a pencil.

Dejima’s website calls the International Club “the place for foreign residence and Japanese People to Develop the relationship.” Having learned almost as much from these two pieces of paper as from trying to communicate verbally with Miharu for three days, I’d say the tradition is still going strong.

No Japanese people were harmed in the making of this blog post.

Thanks for reading! Follow on Twitter or Instagram @gregnasif