Golden Week is vacation time in Japan. During this nationwide string of holidays in the first week of May I had the opportunity to visit South Korea, with my friends Ian and Seth.

Korea has a rich culture. The food is delicious, the history is fascinating, the landscapes are stunning, and the girls are beautiful, even if they weren’t all that interested in talking to me. South Koreans may not be happy, however, with the simple fact that the most memorable experience of the trip for me was a daytrip to see the Demilitarized Zone, also known as the DMZ, and the weird country to the north of it. With my own eyes, I looked upon North Korea.

The Korean DMZ is one of the most interesting places I have ever seen. It is noteworthy for the darkest of reasons; a lot of people died, a lot of people suffered, and an entire culture is bitterly split in half over this 500 mile-long and two-mile wide stretch of dirt and trees, ironically termed the “Demilitarized Zone” despite being the most heavily fortified border on Earth. For that, I can’t speak too positively of this experience. But I can definitively say I enjoyed being there for a couple hours far more than my entire day spent at Universal Studios Japan a couple months ago. Then again, I’d spend another couple hours over a seatless Eastern toilet suffering the side effects of authentic extra-spicy Korean kimchi before getting in one more line at USJ.

After arriving in South Korea, Seth and I enjoyed hikes up towering mountains in perfect weather with stunning city views, ate massive feasts of delightfully spicy food for much cheaper than meals usually cost in Japan (where spicy food is rare), dove headfirst into a vibrant party scene, and walked through many stunning palaces in Seoul, one of the largest and densest cities on Earth. In anticipation of these distractions we made the mistake of looking up DMZ tours a little late. With only a few days in Seoul, it was too late to book a tour to ‘Panmunjom,’ the famous Joint Security Area with a presence in both countries.

There, under strict behavioral guidelines, tourists can see North Korean soldiers with their own eyes and set foot on North Korean soil. Losing that opportunity will haunt me… until I visit North Korea… soon enough.

Instead we accepted a measly tour of every other location of interest within and near the DMZ.

Learning on arrival that we would be monitored by one tour guide for our entire journey initially concerned me. In the past, I have sometimes become frustrated with tour guides who don’t speak English as a first language, because they can rarely share information as fast as I can learn it myself. In Europe I probably frustrated many of my friends by abandoning tour groups in museums (and getting lost on others), and I’ve even criticized tours in print. But lovely South Korean Ji Yeon, the young guide and North Korean observer, proved me wrong.

I mostly remember those who teach me by what of their lessons I later pass on to other people. I find myself sharing things Ji Yeon taught me with many people, even without talking about my trip to Korea, and now, as you will see, I will share her teachings with my billions and billions of readers.

She was electric. Ji Yeon’s passion for her work, for the South’s defiance in the bloody wake of invasion, for her people, and for their trials and difficulties, spoke of a native, lifelong devotion to the political subject at hand. Her lectures felt more like an educational rally. Her English was excellent; she was pouring knowledge into us, and only my own fascination with North Korea allowed me to keep up. I felt rather like Homer Simpson watching a sandwich being made, and I’m sorry, but I can’t find the awesome clip from The Simpsons to back that up on YouTube. Stupid 1990s. (UPDATE: I found it!)

Ji Yeon never shied away from answering our questions, even when I left my friends, sat next to her, and buried her with every curiosity I ever had about North Korea.

Something I did not expect was that halfway through the trip, I would run out of questions about the hermit kingdom, despite it’s being within earshot. Eventually I was left with “What’s going on up there?”

The whole time I worried if my questions might offend her, but she did an excellent job making me feel at home in the world of North Korea’s observers. She was excellent at balancing her logic and passion. Mostly I remember her conviction when she shared with us a profound idea in passing:

It was Germany and Japan who lost the war, but it was Germany and Korea who got split.

Italy sneaks away as usual.

Propaganda Village

In and around the DMZ we visited several interesting sites, including Imjingak Park, the Unification Bridge, “The Third Tunnel,” Dorasan Station, and Dora Observatory.

Dorasan Station is a story of Korean frustration. It is the northernmost and final train station in South Korea, on a track that continues through North Korea and joins up with the famous Eurasian Railroute in Vladivostok, which theoretically could take a traveler from Seoul to London. South Koreans place a lot of weight on being cut off from this line. The interesting lesson here is that South Korea, for the last 65 years, has effectively been an island nation. It was decorated to this effect and good enough for a nice stamp in my journal.

The Third Tunnel was particularly fascinating, as it was originally dug by North Koreans toward Seoul as a secret invasion route, before being exposed by a North Korean civil engineer when he defected to the South. Some of the tunnel’s interesting traits:

-

It is so named because there are four discovered tunnels. There are probably more undiscovered.

-

It slants three inches vertically per thousand horizontally, down toward the north, so water can be drained out by the invaders.

-

Some of us had to crouch to walk through it, but the malnourished North Korean People’s Liberation Army is, on average, the right height to march through it upright. 30,000 of them could theoretically pass through it per hour.

-

It is coated in coal dust. As the South Koreans were blasting into the tunnel, the Northerners hastily coated the walls to disguise the tunnel’s purpose, although the region has been known for over a century to be barren of coal.

-

The tunnel was abandoned so hastily by the invaders, they never cleared the tiny forward blast holes, which clearly indicate the tunnel was directed toward Seoul, just 50 miles away.

At the northern end of the tunnel was a booby-trapped wall built by the South Koreans, barely 100 meters from the underground border with North Korea. With a small hole clear to the mysterious north, beyond which no South Korean has ever passed, and where photography was forbidden, I couldn’t waste the opportunity to speak to the subjugated masses, who were obviously all listening.

“Annyeong haseyo! (Hello!)” I shouted, hearing my voice echo hundreds of meters into North Korea. The South Korean tourists I was with started laughing.

“Please!” I continued. “Please, tell the Dear Leader to stop eating cheese! He is so very fat!” At this, an old South Korean man roared with laughter and clapped me on the back. Feeling satisfied, I turned around at last to return to the Earth and see North Korea in the flesh, super proud of myself for the great service I had rendered to the democratic world.

The next stop was the Dora Observatory, a military outpost overlooking the “Demarcation Line,” or border with North Korea.

A naked-eye view of North Korea. The border is in the trees, and the end of the DMZ is where the trees end.

With my own eyes I looked upon the most oppressive regime in modern times. I could see through the set binoculars the village of Kijŏngdong, better know as “Propaganda Village” set up by the North Koreans within the DMZ, looking comfortable, manicured, and posh from the South.

But it’s fake.

There are telling hints that, until recently, the village was never occupied. It’s packed with trees, for example. According to Ji Yeon, the North Koreans burn lumber for heat. The Dora Observatory overlooks a wide North Korean valley the size of a metropolitan city, and yet Propaganda Village seems to have some of the only trees in the entire region – including the slopes and summits of the surrounding mountains. Burning lumber for heat would also produce flickering lights into the night, but for four decades, past 8:20 PM, there wasn’t so much as a nightlight in a single building. In fact, at that time, every light in the village would turn off simultaneously, as if it was one giant Christmas decoration with a single switch.

Propaganda Village. These photos were shot through binoculars on a hazy day, and are edited for clarity.

The village was set up by North Korea’s propaganda ministry, during the early days of the Korean split, when a resumption of hostilities was a more realistic fear (it’s no longer a realistic fear in South Korea). At the time, both economies were in hot competition, with the North’s actually off to a faster start, and world opinion was more divided on which was the better – or worse – place to live. Each side fought for the hearts and minds of the entire Korean people, so the North built this beautiful village – the Great General’s paradise – in clear sight of main installations of the South Korean Army, into which all South Korean men are still drafted.

It’s hard to describe how creepy this place was to me. In Propaganda Village, every building faces South Korea. While propagandist loudspeaker broadcasts blare from the village singing the praise of the Great Successor, the unfittingly well-groomed buildings simply stare at the object of North Korean desire – free Koreans to be subjugated. The apartment complexes and halls, schools and parks, beautiful and clean on the outside, almost seem to smile at the southern border, inviting their democratic neighbors into their single-party dream, and yet warning them continually of the nightmare from the North.

The Flag Pole

Most prominently in Propaganda Village one can see one of the world’s tallest flagpoles. In a tit-for-tat race, the North and South built flagpoles of competing heights, until the North built one half as tall as the Eiffel Tower. South Korea didn’t bother to match it.

“We don’t care anymore,” Ji Yeon said, with a slight smile.

Indeed, South Koreans have a lot to be proud of. While North Koreans died of starvation by the millions in Pyongyang and other wastelands in their expired country, The Miracle on the Han River saw Seoul rise from the ashes of the Korean War, building massive skyscrapers over vibrant nightlife, with world-class restaurants, bustling factories, speeding trains and, yes, a lot of really good food.

South Korea is a prosperous nation.

But it’s all surrounded by military bases. The North still stands, still keeps the world on its toes, and still has a bigger flag pole.

What do you think? Did North Korea really win that race? Or did giving up show that the South had better things to do?

–

–

Beyond Propaganda

With the battle of economies ending in the most lopsided victory in the history of competition (and no, I won’t post that satellite photo of Korea at night, it’s iconic and if you haven’t seen it you wouldn’t have read this far into my blog post), the countries have begun to cooperate . In recent years, economic collaboration with South Korean companies resulted in actual North Korean workers being moved into Propaganda Village for the first time, perhaps in a northern effort to pretend it was occupied all along. But obviously, this community is not representative of how most North Koreans live. Luckily, the observatory provided a better view than perhaps the northerners realized.

In the bare areas just outside the village are the many small huts where more North Koreans actually live. And beyond this area I could see “authentic” cities, towns, and small communities, with desolate, black, soot-stained buildings and the lifeless aura that accompanies drab Stalinist Architecture. Straight ahead, was the boxy, short industrial center of the one city in view – Kaesong, the third largest city in North Korea, the only city to change hands in the Korean War, and the unluckiest city in history. Through the smog coming in from China I thought I could make out a famous statue of… someone. There are over 500 statues of Kim Il-Sung in North Korea. If Joe Paterno taught us anything, it’s that you should wait until someone dies before you talk about making a statue of them.

To the west was “the authentic village,” as Ji Yeon termed it, a small collection of buildings at the foot of another treeless mountain. Some buildings needed paint jobs, while others looked burned out entirely. The sight of a moving car there was surprising – let alone two. Moving cars require gas. Gas requires money.

According to Ji Yeon, the country does have some economic activity – for the rich in Pyongyang, and for the poor, through the black markets from China. So perhaps these cars belonged to elites. Perhaps they belonged to the military. Maybe the drivers were black market dealers. Very plausibly, they were all three.

Leaving the DMZ

I had to wrench myself away from the balcony at the Dora Observatory. Like Harry Potter before the Mirror of Erised, I wanted to sit for hours and just stare at the object of my heart’s deepest desire: a most interesting place to travel. But the bus was starting to move.

So ended the trip to the DMZ, the most stimulating part of my Korean vacation. It was surreal. Looking over the ridge, at the world’s tallest flagpole flying North Korean colors, at the sad cities and villages, or at the cars driving along the feet of treeless mountains, I tried hard to appreciate that 24 million people were living what they understood to be normal lives, so close to me, when those lives were so dramatically different from my own. But maybe some experiences weren’t so different. They were experiencing the same weather as me, saving or spending money like me, and maybe curious about the world just like me. This juxtaposition couldn’t fit in my brain. Often when confused I bullied Ji Yeon with more questions. She never failed to satisfy.

Ji Yeon also told us the Kim regime may collapse in 5-10 years, and that worldwide media and cell phones with connectivity through China and South Korea continue to trickle in through the black market. The effect this may be having is to irreversibly break the government’s propagandist spell on its population.

The winds of change may be coming – meaning I need to visit North Korea as soon as possible.

After returning to a vibrant South Korean scene that, but for being surrounded by military installations would seem to have moved on completely from its wartorn past, I found I couldn’t get North Korea out of my mind.

The Rest of South Korea

Though ruled by the Japanese for half a century, who attempted to force the Japanese culture and language upon the natives, the Korean people resisted most Japanese traits – they are not work-crazy, and they are not freakishly polite. Of course, they were generally kind to us. But their kindness was more genuine, as opposed to the religious devotion to servitude and submissiveness one encounters in any Japanese shop or restaurant.

Old retired soldiers sometimes stopped me to talk about American and Korean military history, or to just be friendly with me in general. They always expressed gratitude to me, to which I sometimes awkwardly responded that I never served in the military, but my father, grandfather, and many uncles did, and two great uncles served in Korea in particular.

In one case, a soldier on the street happily let me play with his pet bird, while telling me how much he appreciated the American military and enjoyed serving with them. And no, he wasn’t looking for money.

In another case, in response to “We’re tourists,” a taxi driver giving us a ride to a traditional village casually blurted out, “I was a soldier!” In a long passionate rant he told us of his military service 50 years ago, in which he served with American soldiers patrolling the DMZ. I could not waste this opportunity, to talk with an old Korean man so clearly interested in history like me. I asked him as sensitively as I could about the defining conflict of his modern nation. Though forgotten to many in the United States, the Korean War was one of the most violent conflicts the US military ever participated in, costing nearly four million lives – almost all civilians, many of whom were slaughtered in successive massacres as each totalitarian government, North and South, gained control of most of the country at some point.

“Everything was destroyed…” the man said somewhat sadly, before changing back to his positive tone, stammering “We don’t forget!” for the 20th time. “We don’t forget the Americans! 50,000 died for Korea!”

“Everything was destroyed…” the man said somewhat sadly, before changing back to his positive tone, stammering “We don’t forget!” for the 20th time. “We don’t forget the Americans! 50,000 died for Korea!”

He later elaborated a little more – explaining that his family evacuated from a devastated Seoul, which changed hands four times in the war. A young boy at the time, he was luckier than many of his neighbors in Seoul, whose population dropped from 1.5 million to 200,000 starving refugees.

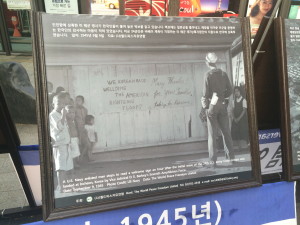

These historical discussions were entirely initiated by the Koreans each time. I wondered how often these people find foreigners like me, who actually care – a lot – about what they have to say. For me, a history nerd, it created a welcome atmosphere in Korea. It drew a contrast with Japan, where the forward-focused Japanese discuss history less frequently, and in which any mildly humble American nonetheless encounters a little awkwardness now and then stemming from the Allied destruction of these islands in World War II.i During the close of that war the Americans liberated southern Korea from the oppressive Japanese colonial forces, and they were welcomed with big signs like “Welcome US Army soldiers: Apostles of Justice!”

The experience with the old man in the taxi – who took a break from his storytelling to rip on the English skills of the monolingual Japanese people – knocked me further out of reality, from which I was already tossed by the DMZ visit. And in the process, I hardly noticed how cheap the ride was. Korea is a lot more affordable than Japan, and this also manifested itself in cheap souvenirs, trains, and huge dinners, cheaper than Japanese lunch specials, with free sides.

I really want to write more about the beautiful landscapes and stunning palaces around Seoul, but what could words do for that kind of beauty? Look at my pictures or visit. Those are your options.

I didn’t think Korea could get any better, until I went to Busan. Keep all the great deals, friendly people and city life, and add in beautiful beaches and the relaxed atmosphere of a coastal city. For someone who has lived on Cape Cod, it felt like home in many ways.

I was and am really happy with the trip to Korea, planned late yet lived out so incredibly well, and I want to go back. I know for a fact Ian and Seth would say the same, in case you forgot they came with me, as I haven’t mentioned them since the second sentence of this ridiculously long blog post.

At the crossroads of ample, spicy food, beautiful women, stunning landscapes, elaborate palaces, skyscrapers and blocks of wild nightlife unhindered by a huge military budget, genuinely good, passionate, nice people, and a patient, forgiving, yet vigilant tolerance and perspective of their peculiar neighbors, the South Korean people have put quite a country together.

Next up is their quirky neighbor.

Thanks for reading. Follow the adventures on Twitter or Instagram @gregnasif. Leave a comment or email gregorynasif@gmail.com for feedback.

More photos:

- War Memorial of Korea

- Geongbukgung Palace

- Found five or six of these guys, more than in 15 months in Japan.

- Geongbukgung Palace

- Changdeokgung Palace

- Geongbukgung Palace

i I have, at times, been asked by Japanese adults my opinion on the atomic bombings, both before and after visiting both peace memorials and museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This usually involved a discussion topic in an advanced English class. Although I spoke honestly, I have never had to exercise so much delicacy in my speech.