Day Four

At nearly every single visit for our last two days in North Korea, various tour guides attempted to impress upon us the extent of leaders Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il’s “on-the-spot guidance” in moving North Korea forward.

The first journey of day four would be by subway.

The Pyongyang Subway is the deepest on Earth, serving as a potential shelter from nuclear warfare. The escalator journey took ten minutes and led to some ear-popping.

To counter conspiracy theories that the Pyongyang Metro was only one stop long, tours of the metro consist of two legs – one stop on a traditional train, and three stops on one of the modern ones.

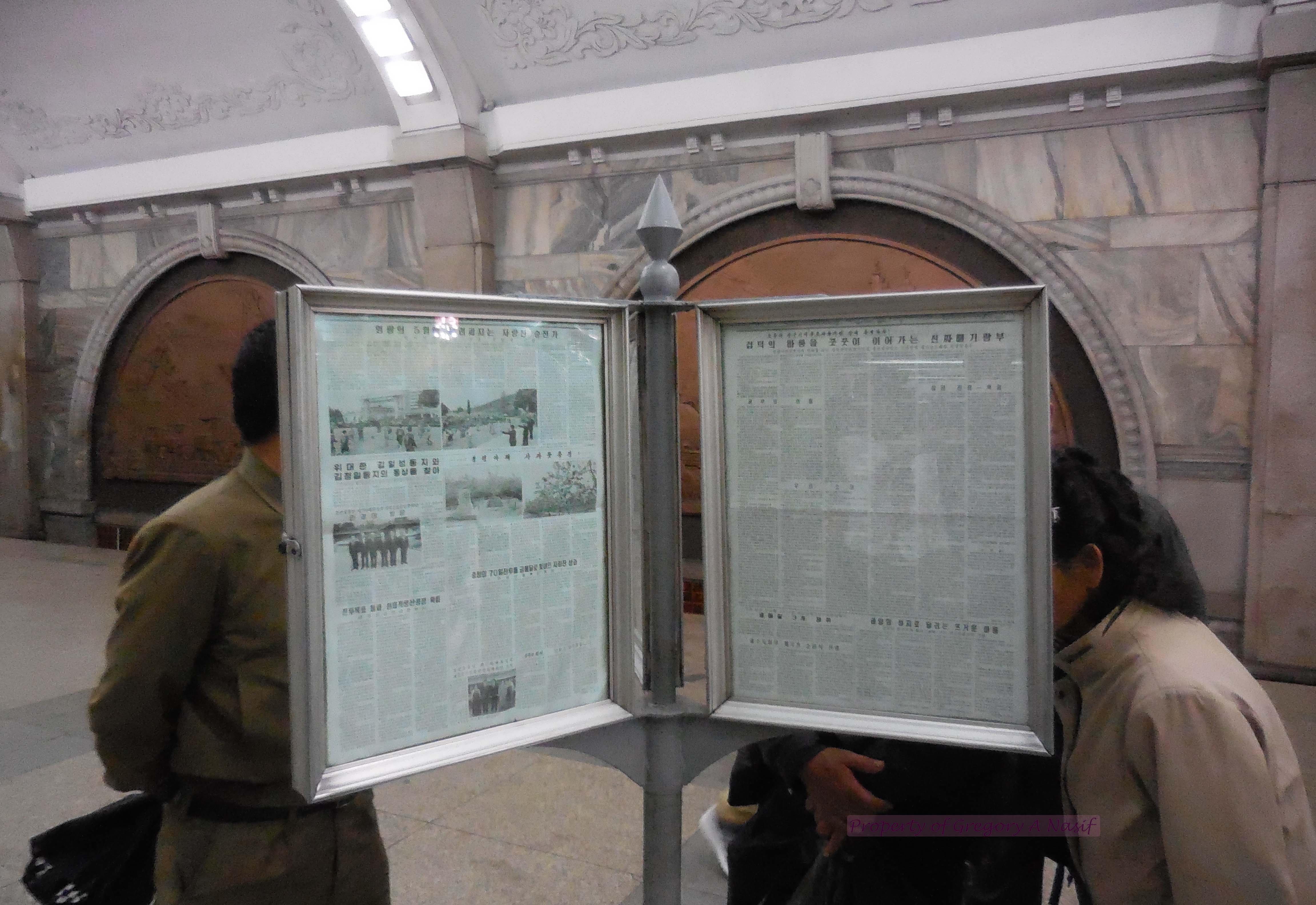

The stations were full of propaganda.

The guides spoke long and elaborately about the efforts to construct the metro and design the trains – all done, of course, with the Kims’ on-the-spot guidance (there is little mention of Soviet assistance in building the system).

There was a bizarre incident just one minute into our first train ride.

We boarded the train, and from the inside looked like so many this writer has ridden all over the world, though of course with one extra detail:

In a country with so few foreigners and so much exclusivity, it was a subtle surprise that other travelers weren’t eying us like their leaders’ portraits. It was almost as though they’d all expected us.

Except for one, short old lady, staring at Charles, from the Netherlands.

She was short, hunched, wrinkled and toothless, thin – almost emaciated, and wearing the drab green colors as almost every other civilian.

Charles was tall, rosy white, in western clothes, the most foreign-looking man in the history of that train ride, and he was her target. Standing idly, sensing a drift, he turned to find the humble figure standing right behind him, eyes now locked onto the palm of her hand, into which she was pressing a finger. She was tracing a word or symbol that no one, least of all Charles, could understand. So she intensified, closing in, raising her hand higher, digging her finger deeper into her palm, her face contorted with determination.

She drew the same symbol again.

Confused and slightly panicked, Charles looked side to side, wondering what to do. The woman had him pinned against a corner. By now, our tour guide had noticed, as had another young civilian, who got to her first. As the old woman drew the same symbol a third time, the young man and soon two more civilians stepped in front of her and tried to pull her away. This quickly escalated into a restraining operation, as the woman struggled and flailed, determined to get back to Charles and continue drawing her point.

The three men were still restraining her as our guide, keeping composure, ushered us off the train at the next station for our journey’s pre-planned intermission.

From then on, quite hopelessly, the tour wondered who that woman was, who those men were, and where she went after that – indeed, where she is now. I am sure we will never know.

More propaganda art was spread about the next station.

The “heralding” seems to be a favorite of communist propaganda artists.

The next journey was three stops by a more modern train, recently purchased from Russia, and installed with on-the-spot guidance.

Scene from the station:

It was equipped with TV screens. In China, Taiwan, and South Korea, screens like this are known to play advertisements. But only one entity needs to be advertised on the Pyongyang Metro.

You many want to lower the volume for this:

Eventually we arrived in another district of Pyongyang, near the Arc of Triumph.

Nearby there were preparations for the upcoming Seventh Congress of the Worker’s Party, with thousands of people doing a practice rally.

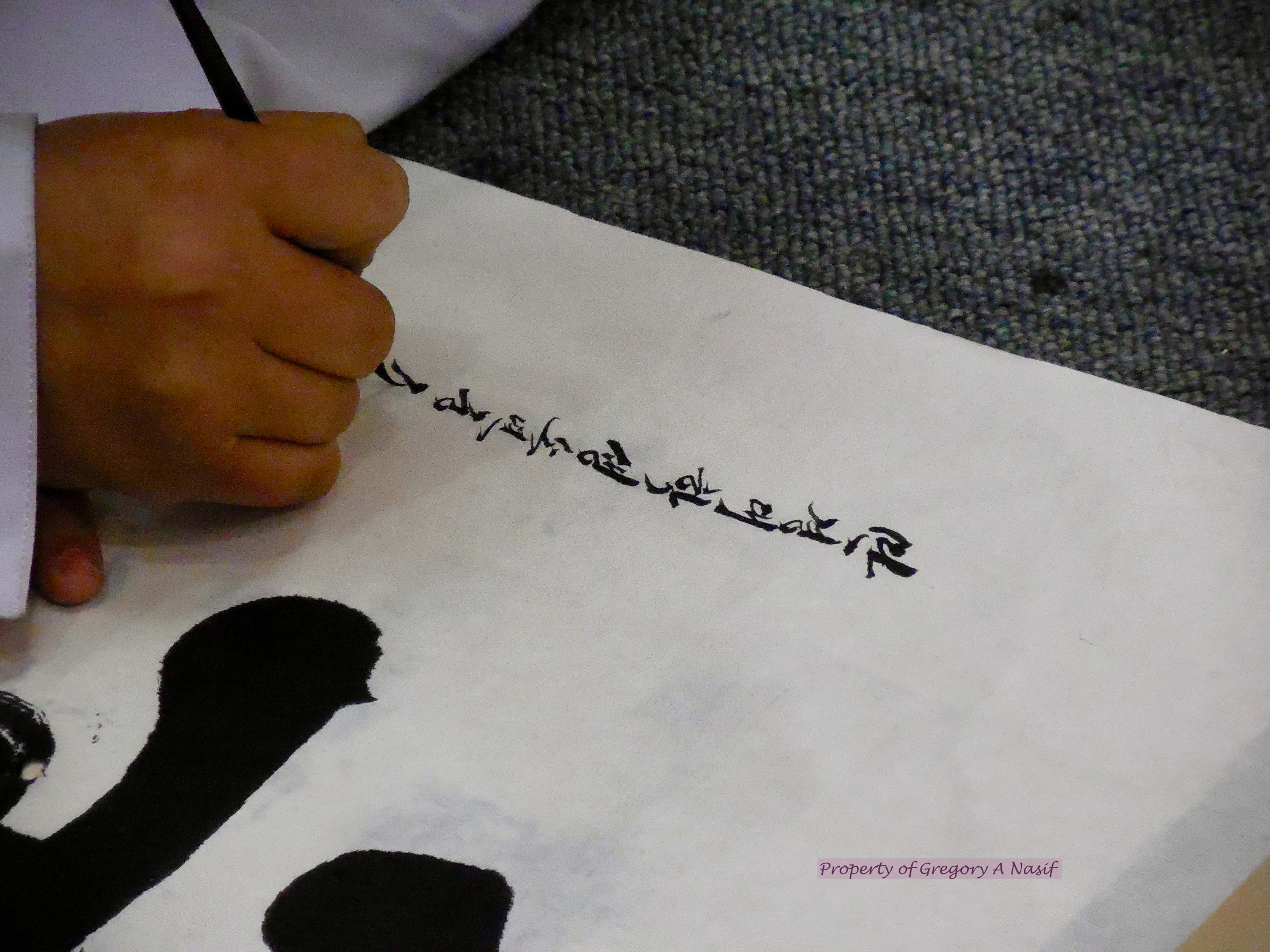

Next we visited an art gallery, constructed with on-spot-guidance, featuring paintings painted with on-the-spot guidance.

We were introduced to several of the talented painters, including a smiling, genial old man, and a scowling, sardonic young woman.

The actual price of paintings bigger than most kitchen tables was often less than a dollar, though tourists were required to pay roughly 8000% markups.

This painting made me laugh:

From here we went to a gun range. It was staffed by pretty women in full army attire.

I was a poor shot. Our tour guide, however, hit every target.

Roger, from the UK, opted to shoot a pheasant. Hit one, and it would be served that evening for dinner, they explained.

A few minutes later he emerged with some staff, holding the petrified bird as they bagged it up.

I did not see any bullet wounds. But pitying the bird, I suggested they wring its neck and finish it off. Perhaps to keep it fresh, they ignored me. And they soon regretted that decision.

“It escaped!” I heard one yell as we walked to the bus. I joined Roger and watched the ensuing hunt.

Picture the scene: four gorgeous North Korean army captains chased a pheasant around the grounds laughed on by two western tourists with all the time in the world. It could only have been better with Yakety Sax playing them on.

After the gun range, we went to lunch, where the driver and cameraman argued very loudly over something. The camera man would say something and make big gestures, while the cameraman angrily denied it, waving his hand and looking irritated.

“I killed 50 Americans!” the bus driver said, presumably.

“No way.”

“Really! They were all coming at me with grenade and rocket launchers! And I stabbed them all! With a knife!”

“Shut up!”

“Really! I stabbed them! In the head! Then, I took all of their women and made them all my wives!”

The cameraman shakes his head, a skeptical look on his face.

“Then I booby-trapped an entire division, rigged four tanks to blow, and burned 2000 books on democracy in one hour! It happened exactly like that!”

“Whatever…” the cameraman obviously said, waving off the driver.

At least, that’s how we think it went down.

After lunch the tour went to a place claimed to be the birthplace of Kim Il-sung, born, presumably, with on the spot guidance.

This location is widely disputed, making this visit a bit of a dull means of seeing how they conduct their propaganda.

They opted for realism, presenting Kim’s birth and upbringing as humble. It was barely a shack, with portraits of his family.

Next.

The cold and rain settled in as we visited a bowling alley, built with Kim Il-sung’s on-the-spot guidance.

Then to the Myongdae Children’s Palace, built with on-the-spot guidance.

We were guided through the building by a thirteen-year-old girl.

The massive palace looked more like a national capitol than a children’s after school program.

Inside, kids, hard at work, didn’t look up or acknowledge us. When I used a tour guide to ask kids basic questions, they’d respond extremely shyly, only saying hello when pushed to do so by the guide.

The children were producing high quality works of art, presumably without being paid. One wonders to what degree they chose these pursuits, or what happened with their products.

Then we were led into an auditorium packed with North Korean youths. They, too, would not respond to a word spoken to them, in Korean or English. With scared and stressed facial expressions, most only stared straight ahead and ignored our greetings, a few of the braver ones smiling silently.

The show, meanwhile was stunning. Kids aged five to sixteen put on spectacularly diverse and elaborate performances, with complex dances, lights, stagecraft, moving parts, musicians, a comedy routine, costumed plays, solos, ballet, etc. It seemed they practiced their routines full-time. With on-the-spot guidance.

At the end of the last performance, an image of Kim Jong-un took over the screen, and every student in the auditorium cheered for the first time (and loudly).

If you have the time:

At the conclusion, a western science delegation mounted the stage to deliver flowers to the students. We exited with this delegation; among them were three Nobel prize winners, including the 2004 Laureate in Chemistry, Aaron Ciechanover from Israel, who, on the way out, asked me some questions about our tour group.

Science delegation, with Aaron Ciechanover (center-left, back)

We then left this odd building and set out for Nampo, a rural district southwest of Pyongyang. The drive once again displayed a lot of rural poverty, but the darkness and rain prevented most photos. There was a lot of propaganda. Some of the murals were lit, but as it got dark, and cold, not a single light went on in a single house.

We spent an interesting night in the countryside.

The lodging in the middle of the rainy windswept forest looked like the lair of a Bond villain. It had a predictably ominous entrance hall, with tall ceilings, doors big enough for a giraffe to pass through, and paintings that could probably sell for more than the yearly income of the entire region.

That night, our cameraman and bus driver organized a traditional kerosene-fired clambake under a concrete awning. The tradition was heavily drowned in soju.

Looks like…

There was a security breakdown at this lodge for me.

The room was quite hot, and despite thirty minutes of fishing around, I could not figure out how to turn off the heat. So I opened the porch window, downwind to the now weakening storm, and fell asleep to the cool backdraft that crept into the room.

I awoke at four in the morning to find my room hot again. The porch door was closed – but the door to the hallway was wide open, even though I had locked it before I went to bed.

Alarmed, I checked all my possessions, even the photos on my phone and camera. Nothing was changed. Someone had come in to close the porch door. In this country, in this moment, I had to accept that a locked door was beyond my privacy rights.

Day Five

By morning the howling wind and rain had ceased. As we drove through the countryside, the evidence of it remained. There were downed trees. But something was amiss about them.

By morning the howling wind and rain had ceased. As we drove through the countryside, the evidence of it remained. There were downed trees. But something was amiss about them.

Trees that had survived stood upright and healthy, sometimes missing a branch or two. But there were no branches on the ground; instead, trees on the ground were bare trunks. There were no branches scattered about, even though the trees had clearly only fallen the night before.

Some of the mountains in this area were, as usual, devoid of trees, but others were more covered with young sprouts.

“Why do some mountains not have trees?” I asked the tour guide, knowing the answer, and wondering if she would answer honestly, which she did.

“They were taken down, for making fires,” she said. She further elaborated that Kim Jong-un’s government, in a green initiative, banned private logging, halting the deforestation.

“Then how are people heating their homes?” I asked.

“I think coal” she said. While coal is abundant in North Korea, it is still expensive. And as we passed an old woman trying to haul off an entire 12-foot-long tree trunk from the side of the road, I suddenly realized why it and every other felled tree was barren of branches at nine in the morning.

Throughout the morning drive we also saw women picking things in the grass; we do not know what.

Sometimes townspeople patched up roads ahead of us, almost like they were expecting our bus to come through.

Ahead, today’s destination was promoted as a feat of North Korean engineering.

It was a large waterlock and seawall, which served to expand and protect freshwater and farmland in rural southern North Korea.

Inside we watched a video, hilariously narrated in English by a Korean woman with a thick accent, about how North Koreans alone built this massive public project from conception and design to finish. All of it was done with “President Kim Il-sung giving on-the-spot guidance.” During the video, some of us giggled at the mention of that phrase, not unnoticed by the tour guides. Some of us, however, couldn’t be bothered.

The project cost four billion dollars, built in the 1970s. That was North Korea’s entire GDP at the time. It would be like the United States spending $20 trillion on a single project.

I spoke some Korean with this woman:

Our next stop was a “collective,” which is communist speak for a village.

Not this one

This place, in many ways, fit much more comfortably with our stereotypical images of North Korea. Wait for it.

The collective was promoted for its prosperity, and heralded with a massive statue of Kim Il-sung. Once again, the man rules from beyond the grave.

The houses in the village bore many colors. We approached the most colorful building of all – a small kindergarten. The laughter of four and five-year-old children drifted out of the windows on the light breeze.

It was a beautiful day to meet some kids.

The entranceway to the school is heralded by this massive painting:

When you see it

In an upstairs classroom stood eighteen rigid four and five year olds, the cutest little propagandists I’d ever seen.

Courtesy of Berkay Tekin

The teacher sat at the piano and began to play, and the children grabbed us and pulled us into their circle. For fifteen minutes they made us part of their little dance routine, pushing, pulling, and turning us about, little four-year-old hands pressing us around. They had no interest in explaining, they just pushed us around and sang, herding us like toy cars.

Much of the music clearly centered on Kim Jong-un. It’s still stuck in my head.

At the end, as the tour was preparing to leave, the kids waved goodbye, without smiling.

On the way out I played with the kids a bit, giving them high fives and such. At first confused, the children warmed up. An article published in The Washington Post the same day suggested these kids were rigid, emotionless, and hardened. But I saw them laugh, some loudly. I watched them play. I saw them be kids, as kids will do.

But there were other bad omens here.

Kids in America learn various shapes, colors, and fruits.

Apparently kids in North Korea learn various ways to kill an American. This, at least, is what they allowed to be conveyed with this kindergarten visit.

The on-the-spot guidance continued with one more stop at a factory.

We were told this plant, the only water-bottling plant in the country, produced 135,000 bottles a day, in a developing nation of 24 million people. Most people, we were told, boil their water.

The on-the-spot guidance got to be a little much. I haven’t even exaggerated here – they really mentioned it for everything. Engineering (“use the water to help dissolve the rocks!” Kim supposedly said), bowling alleys (the people need entertainment in their daily lives!), kid’s palace (the children need good lighting!), activities at the kid’s palace (sweet melodies can soothe a weary heart!), and on and on. At the factory, it was all the parts and the whole: the construction of the building, the machines, the bottling, the reasoning. It was an orgy of on-the-spot guidance.

Courtesy of Berkay Tekin

So we joined in.

Thanks for reading. Email replies to [email protected]

More pictures:

The universality of this sign was interesting.

Arc of Triumph

May Day Stadium, under repairs

This woman was not happy we were in her studio.

All photos, even unmarked ones, property of Gregory A Nasif unless otherwise specified.