August 2014

The week preceding this story was one of the few vacations Japan seems to tolerate. During that time I took a much-needed eight-day trip to China. It was one of the most exhilarating, dynamic trips of my life, with two of my best friends. We explored many famous sites, ate a lot of different foods, hung out in all kinds of cool, weird, or historic districts, and I felt like I conquered China itself. But on the last day, after a heavy meal at a famous duck restaurant, China fought back. I returned to Japan at the end of the week, with my digestive system in tatters.

I knew asking for a day off was akin to asking my boss to let me punch her in the face. And I knew the company rejected criticism on all fronts.

So I stumbled through the week, gray in the face, taking bathroom breaks between each lesson. But no matter how much water I drank, I steadily approached full dehydration going into Saturday.

The Japanese are a very serious people.

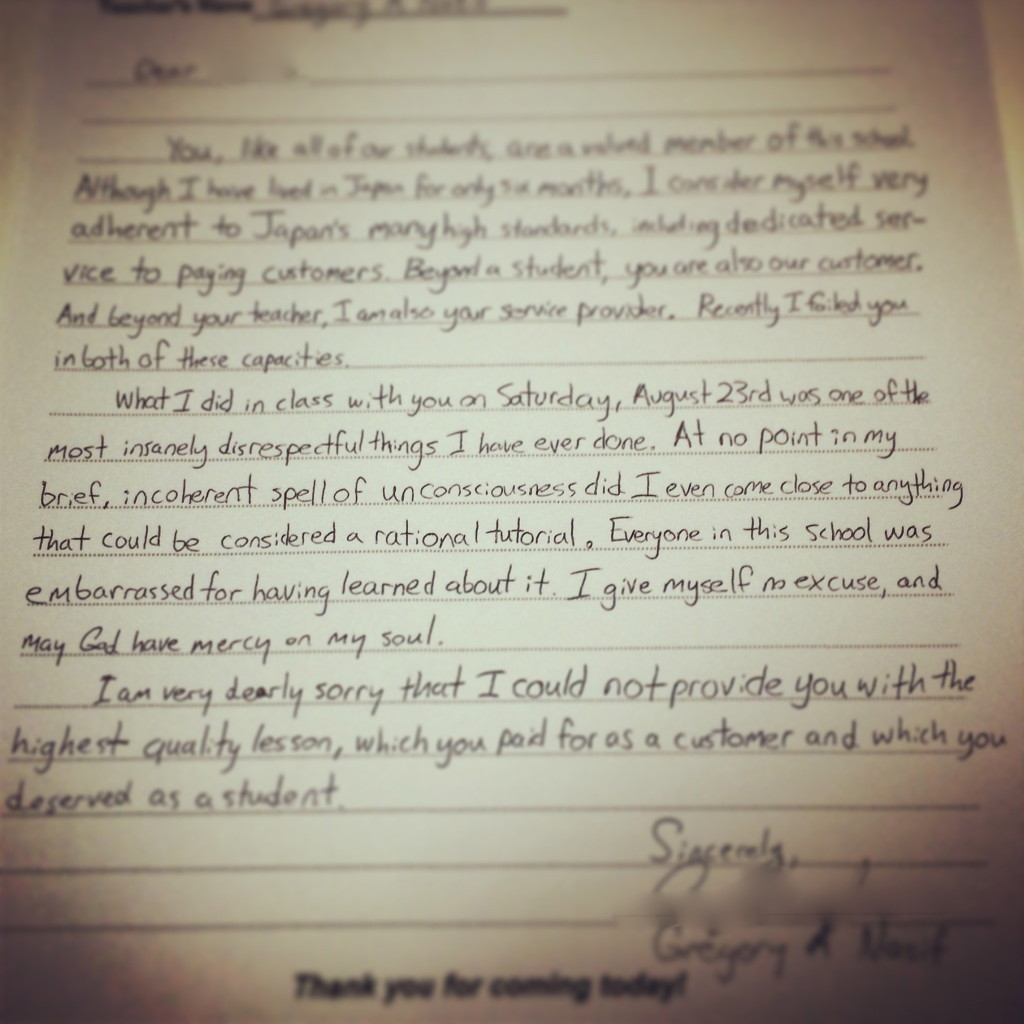

Today you will read the story of the best apology letter I’ll ever write. It’s the story of why I started a new job this year. And perhaps you’ll come to understand why I’m so grateful for how it all turned out.

To follow this story, it is necessary to try to understand the strict and severe nature of the Japanese business environment. I arrived in Japan full of excitement to work and live abroad, but slowly became bitter and negative, a result of 50 hour workweeks, just the surface of a bizarre economic culture.

Individually, Japanese workers are notoriously unproductive, because they spend very long hours pretending to work. Their standards are as plain and raw as their food – show up, applaud the bosses’ decisions, be there a long time, and look like everyone else.

The Japanese tend to work effectively as a single unit. Everyone must work together. The idea of taking time off work is frowned upon, which in Japan is akin to being strictly forbidden and heavily scorned. If you are sick, you go to work, with a mask. If you can’t go to work, you go to the hospital and use your vacation days. And you return as soon as possible. Then you have many thank yous, excuse mes, and apologies to dole out: there is a complete dialect for pleasantries and for being at work in general.

This is perfectly encapsulated in a quick story-before-the-story: weeks before I left the company, a coworker’s father became ill and suddenly passed away. He returned to America, and the bosses later made scathing comments about the time he spent away, which amounted to less than two weeks. When he returned, he was chewed out for not acting thankful enough to his coworkers who helped cover his absence. Picture that: he was yelled at for not appearing cordial.

In this environment I learned how to suppress yawns, which are considered very rude in a culture that doesn’t seem to understand involuntary behavior. Ok, I’m a little bitter about this story.

The Background

This story begins and ends with one former mid 30s student of mine who really liked to complain. About everything.

He complained that the class was too difficult and that I talk too fast. He was in our most advanced discussion class, where I’m supposed to speak with full nuance at natural speed.

He complained that he didn’t understand the material. In my class we discuss politics, social issues, and cultural issues. He doesn’t understand any of these topics in any language. He admitted this on several occasions.

He complained that he was alone in class. I taught the same class an hour later with three people. But he refused to come at that time because it didn’t work with his personal schedule.

He complained that I yawned during lessons. He literally never came without telling me he was tired (assuming I asked), because:

He complained that he had to work 12 hour days six days a week, and thus couldn’t do his homework and spoke very little.

Finally, he complained that he wasn’t learning. He was an intermediate English speaker who needed a grammar intensive conversation class. EFL professionals from both sides of the Pacific have implored him on this. “I know what I need” he would scoff to our counselors, never explaining any more. So he stayed in my class – a political discussion class for fluent English speakers.

It wasn’t so much a negative student that bothered me. It was the cult that came with a business masquerading as a school. The student wasn’t allowed to be the problem. Some might call this a good corporate strategy. I call it a terrible teaching strategy.

So we carried on this extremely difficult one-man show. Today I will call my student Hideki.

Teaching to adults meant my schedule wrapped around the regular business world. After working until 9:30 PM on Friday night, on Saturdays I would work from 9:45 AM until 7:30 PM. Class with Hideki was right after lunch on Saturday, in a white windowless room. I haven’t even started the story yet, and I’m already half asleep thinking about the setting.

Between the illness I brought from China, limited sleep, a class after lunch, the man I was teaching, and the grievances he had already expressed, there was never a better time for this great English phrase that he’d probably never understand:

The Perfect Storm

The Story

In the beginning of this job, I resented that I had to pretend to be happy to see my students. As I came to like more of them I found this problem reduced itself quickly, yet not entirely. Perhaps the last holdout for my inauthenticity, seeming exceptionally tired as usual, ghosted his way through the door, while I fought to remain standing, on a hot humid Saturday afternoon in late August 2014.

“Hello Hideki!” I began.

“Hello” he mumbled back, not looking up.

What was that feeling in my brain?

“How are you?” I asked.

“…”

Surely, I’m just facing usual teaching hurdles. No problems here.

“…”

He still hasn’t said anything. Did he mishear me?

“…”

Man, that lunch was hot. I should eat colder food in summer. But what is that feeling?

“Tired” he finally said.

Empathy kicked in. That feeling was pure exhaustion, gripping my entire body.

“I see. Tough week at work?”

“Eh?” Japanese people think “huh” is rude. Ignoring me is rude too, Hideki.

“Did you have a difficult week at work?”

“…”

I wonder if we could mutually agree to nap for the whole class.

“…”

No! I can’t think of napping. It will make me more tired. Uh oh! *suppresses yawn*

“Yes.”

I wonder if he noticed.

In class we were to speak about the Japanese cultural resistance of sun exposure. Even in this country’s hot, humid summer, Japanese women will cover their forearms with removable sleeves or even jackets, and they usually wear umbrellas (in the sun, it’s called a “parasol”). A quick visit to the beach reveals, not sunbathers as one sees in the West, but a city of tents. Japanese women tend to have extremely high quality skin, but there may be health defects from such limited sun exposure, such as Vitamin D deficiency, which could lead to Osteoporosis. And here, in this short paragraph, we have had as much discussion about this issue as I did with Hideki in a 50 minute supposedly expert-level English class. And you, the reader, contributed about as much as he did.

As we walked up the stairs and into the classroom, I pondered how I would possibly engage him in discussion.

“Did you do your homework?” I asked, knowing the answer.

“I did reading, but, I not understand.”

Of course. I’m sure he read it for ten whole seconds this time, maybe even fifteen.

His sheet was blank. Not a question answered. The assignment was to do “research” on the statement “Japanese people are too worried about protecting their skin from sunlight,” and to “write down some things they find.” He wrote nothing.

Important to remember: Hideki has told me before that he has no interest in science, politics, or cultural issues, which covers literally every single topic in the class. Even if the class were taught in Japanese, Hideki would be just as lazy, clueless, and silent as he always is. And yet he refused to try anything else. Because he knows what he needs.

But he was the one paying to not speak English. So I spent ten or fifteen minutes of trying to explain the reading material to him, sapping most of what was left in my tank. I was running on empty.

Finally I simplified the argument to one question.

“Do you think sunlight is dangerous?”

Maybe if I treat the class like a day on Sesame Street, we’ll be able to keep up with each other.

“Dangerous?”

Yes, dangerous Hideki. Like me attempting to drive right now.

“Ohhh.. I don’t know.”

You know nothing. Especially how hard it is to not… oh god why did I think about… *suppresses yawn*

“Hideki,” I began, feeling desperate. “Japanese people, especially women, need more Vitamin D. Should Japanese women stop wearing long sleeves in summer? Should they let sunlight touch their arms? Is not wearing anything on their arms ok? Japanese women? Sunlight? …” I must have asked this question in eight different ways, with extremely detailed hand gestures. It landed.

“No!” he finally answered. “Only a few minutes of sunlight, and can get heat stroke.”

I was dumbfounded.

“Heat stroke??!”

“Yes.”

At the very least, the shock of this point had brought me out of autopilot, fully back into command of the situation. “Hideki. I walked for ten minutes to work today, and I didn’t get heat stroke.”

“Only a few minutes of sunlight, and can get heat stroke” he repeated.

“Heat stroke? From a few minutes?” Just considering the daunting task of fully challenging this absurd suggestion was already beginning to exhaust me.

“Yes,” said Hideki.

“That seems strange.”

He stared. I don’t have the energy to make him respond.

“Wouldn’t wearing excessive clothes in the heat exacerbate any chance of heat stroke?” I asked, already laughing internally at myself for thinking he would understand any of that.

“Eh?”

“The Sun makes you hot,” I began.

“Yah.”

“Clothes can also make you hot,” I continued.

He nodded.

“So wearing a lot of clothes in sunlight can make heat stroke happen even faster.”

He stared at me. Despite his assents I wondered if anything had landed. So I sat down to try to focus the conversation. This is comfortable.

“But, only a few minutes of sunlight, and can get heat stroke” Hideki said again, before I could reiterate.

Is it acceptable to cry in front of a Japanese customer?

“Wouldn’t more clothes make heat stroke worse?” I tried. I really was trying. Negative questions (Don’t…? Woudn’t…? Aren’t…?) are well below this level. In my mind, I envisioned my argument being contemplated and evaluated. Eye on the prize.

“Ohhhh,” he began. Did it work? “Science study say…” Yes, he’s changing his argument! “… only a few minutes of sunlight, and can get heat stroke.”

It felt like that moment in The Perfect Storm when the sun disappeared before the final wave. He’s not gonna let me out.

“Heat stroke is caused by overheating,” I explained. I had, after all, been surprised many times by what this guy didn’t know.

“Yah,” he said.

“Clothes make you warmer,” I continued. Just like Ernie and Bert.

“Yah,” he continued. I invested all my remaining energy in faith that I would drive the point home.

“So wearing long sleeves and gloves in sunlight will increase heat stroke.”

“…”

“…”

Victory! Time to consider the next point… what was this class about again?

“…”

“…”

“Only a few minutes of sunlight, and can get heat stroke” he repeated.

I went down, but by God, I knew I’d go down fighting. Just like Marky Mark.

“But wouldn’t wearing more clothes increase the chances of heat stroke?” I tried to say.

“But wouldn’t… wearing mo… mo…” is what I actually said, before the boat tipped over at last.

I’m in trouble now.

But I also felt great. I gave it everything I had, and there’s no more satisfying feeling than that.

The next thing I remember, I was brushing off Hideki’s suggestions that I get water. Adrenaline, refusing to intervene earlier, resurged at last. I finished the last few minutes of the lesson, ran off to warn my manager, and prepared for her to berate me later, as, indeed, Hideki would berate her, just minutes after our lesson ended. Ironically he was probably right to do so.

He didn’t come back the next week.

I never saw him again, actually. And yet, for all the firestorm this entire incident caused, it was not why my contract wasn’t renewed. That came the following Tuesday.

“What are you doing in there?” my boss asked of me, spotting me sitting in my classroom during a free block.

“Pondering,” I answered sarcastically.

“No sleeping!” she taunted.

“Come on,” I joked back. “You know I need Hideki’s voice to make me go to sleep!”

She didn’t find that funny. Neither did the district or regional managers. Japanese people don’t like jokes. Come March there would be no more windowless classroom for me.

A week later I was told to write an apology letter to Hideki.

In my heart, I wanted to thank him. His selfish way of life set me free from that horrible, dark classroom, free to enjoy the sunlight once again. To thank him, I hid within my apology letter a thank you note, with a little creative help from a couple friends (previously pictured). And to me there’s no better way to thank somebody than to make them laugh.

I’m not sure he’ll get it. The Japanese are a very serious people.

Thanks for reading. Keep following on Twitter or Instagram @gregnasif.

Email gregorynasif@gmail.com

Hint: this wasn’t from The Perfect Storm.

wow, great human interest story.